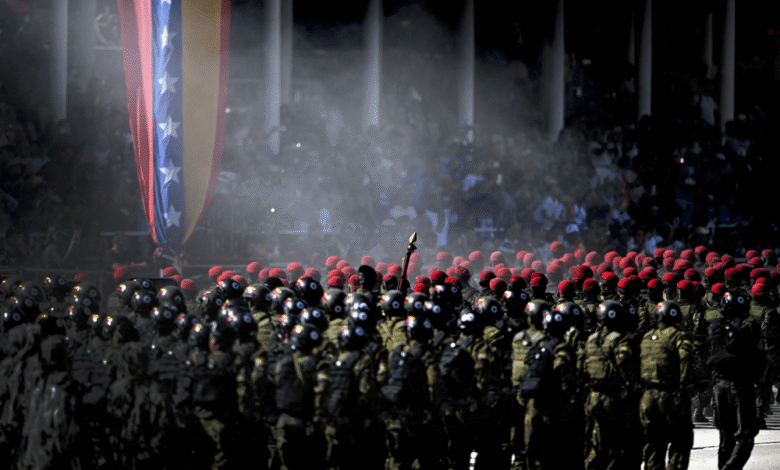

Venezuela’s Military Still Holds the Levers of Power

The United States has arrested Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro, who is currently detained in New York, and everything about the country’s political future is in question. The decisive variable is the Venezuelan armed forces. Whoever takes charge in post-Chávez Venezuela, the military establishment is certain to remain politically active.

The danger is that if civilian leaders are appointed, the military will either overthrow or manipulate them. For this reason, the transformation of Venezuelan civil-military relations, in both form and substance, is crucial to long-term democratic stability. It will require moving away from the current party-controlled military establishment – but also from the civil-military relations of the pre-Chavez era that preceded it.

The United States has arrested Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro, who is currently detained in New York, and everything about the country’s political future is in question. The decisive variable is the Venezuelan armed forces. Whoever takes charge in post-Chávez Venezuela, the military establishment is certain to remain politically active.

The danger is that if civilian leaders are appointed, the military will either overthrow or manipulate them. For this reason, the transformation of Venezuelan civil-military relations, in both form and substance, is crucial to long-term democratic stability. It will require moving away from the current party-controlled military establishment – but also from the civil-military relations of the pre-Chavez era that preceded it.

Aside from reports of a CIA spy within Maduro’s security detail, the poor performance of Venezuelan military forces throughout the January 3 operation was striking.

What we do know is that the president’s direct security detail — a job officially assigned to the Presidential Honor Guard unit — includes several Cuban personnel, 32 of whom were killed during the U.S. raid. This may indicate that Maduro and other senior commanders do not trust their soldiers. Moreover, the Venezuelan air force and army were unable to prevent the incursion of US helicopters carrying special operations forces or destroy Russian-supplied air defense systems, which also exposes weaknesses in readiness and equipment.

However, although the military has proven incapable of defending the nation, it is nonetheless a major political player, as three data points revealed. First, consider Maduro’s appointed Defense Minister, Vladimir Padrino López, announcing his support for Vice President Delcy Rodriguez on January 4 — before she became acting president on January 5.

Second, upon assuming the presidency, Rodriguez appointed Major General Gustavo González López as head of the presidential guard of honor. Gonzalez Lopez is the equivalent of a four-star army general, a former head of the National Intelligence Agency, and a former commander of the pro-regime Bolivariana paramilitary force. Third, remember that the Interior Ministry is headed by Maduro appointee Diosdado Cabello, who is known for his close ties to the military and who also remains loyal to the regime.

This merger between the party and the military did not originate with Maduro, but in the pre-Chávez era — in Pontoviejo’s democratic regime, which was disrupted by a series of coups beginning in the late 1980s. The first little-known coup that Venezuela witnessed in October 1988 tanquetazoIt revealed deep-rooted institutional problems in the army. The second famous coup was led by Lieutenant Colonel Hugo Chavez of the Venezuelan army in February 1992. Although the February coup failed and its leaders were imprisoned, another failed coup, led by elements of the Venezuelan Air Force, followed in November 1992. The coup leaders fled to Peru, but both groups of 1992 coup plotters were later granted amnesty, and Chavez joined civilian politics.

These coups occurred because civilian supremacy in Venezuela’s pre-Chávez democracy was an illusion. The 1958 Pontoviejo Pact, a power-sharing agreement between three elite-dominated parties, allowed the military to retain dominance over national security issues, avoid scrutiny, and foster personal relationships between senior officers and politicians.

This arrangement meant that even when civilian rulers attempted to create a professional army, accompanied by strict areas of separate expertise, professionalism never replaced praetorian tendencies within the Venezuelan army. Civilian oversight was waived, as was budgetary oversight; At the same time, as scholar Harold Trinkunas explains, the General Staff was replaced by a Joint Staff to thwart central command and inter-service cooperation. Among the ranks of the Venezuelan army, as researchers Hernan Castillo and Leonardo Ledesma point out, loyalty to the constitution “does not necessarily mean effective civilian control over them and their true submission to civilian authority.”

This contradiction between the appearance of civilian superiority and its reality was obscured for two decades or so by the oil wealth that ensured popular legitimacy, as well as high salaries and benefits in the military. In the late 1980s, due to growing popular unrest in the wake of austerity measures that included cuts in military benefits and massive corruption scandals, even that superficial civilian superiority collapsed. Military interference in politics escalated, culminating in the coups that brought Chavez to power.

There are two institutional aspects of the coups that took place between 1988 and 1992 that reveal the harmful dynamics of the civil-military relationship at that time. First, the military leaders were aware of the growing opposition against civilian politicians by the coup plotters, but they did not report it to the civilian leaders and neither the military nor the civilian leadership took any preventive action. At the same time, civilian leaders in the Pontoviejo regime gave up supervision of the army in exchange for its loyalty. For example, the Secretary of Defense was a serving general, and the military budget lacked civilian oversight—even though the Constitution required a civilian to be in charge and provided for civilian oversight.

Second, the coup attempts in 1988 and 1992 were led by mid-ranking officers, that is, majors and colonels, not generals. Despite civilian and military losses in particular in the two 1992 coup attempts, the perpetrators of these attempts were released and asked to join politics under interim presidents Ramón José Velázquez and Rafael Caldera. A system in which training and promotions were professionalized up to mid-ranking officers, while senior officers enjoyed clientelistic relationships with politicians who interfered with promotions, was dispiriting to aspiring junior and mid-level officers.

These weaknesses, combined with growing popular opposition to the Pontoviejo regime, culminated in popular protests, riots and looting in Caracas against austerity measures, especially increases in gas prices, in 1989. The uprising was crushed by the police and army, but it left an indelible mark on Chávez.

The prevailing institutional arrangements created and expanded by Maduro have consolidated single-party control over the military. Their strategy since the failed coup against Chávez in 2002, the last of the Cold War, has included a combination of surveillance by intelligence services, promotion based on political loyalty rather than merit, changing non-commissioned officer promotion structures, opportunities for corruption through the trafficking of drugs and other goods, and the creation of counterweight forces such as the National Guard and colectivo militias.

Buying loyalty through promotions and corruption has produced ludicrous results, such as a roughly 2,000 generals and admirals in the army and a combined 150,000-strong National Guard, with small commands and a navy with few seaworthy ships. To put these numbers in perspective, Brazil – which has the largest army in South America at 366,500 soldiers – has about 403 such officers.

The merger between the party and the army has ensured loyalty to the leadership for a long time. Now things have changed again. But whether we are currently witnessing regime change in Venezuela or something else, there is a chance that the military will collapse along party lines, increasing the possibility of rebellions and civil war.

Venezuelan opposition leader Maria Corina Machado, who was apparently rejected by US President Donald Trump as an alternative to Maduro, had previously presented her plans for a post-Maduro future. She said the new government must reform the army and police “so that their mission, their sacred goal and their constitutional duty are to defend all the people of Venezuela as well as our national territory.” However, doing so requires moving away not only from the party-controlled military establishment of the Chavez-Maduro regime, but also from the civil-military relations of the Pontoviejo era. Machado ignored this last aspect.

If political parties lose popularity, a return to civil-military relations established by the Pontoviejo regime could destabilize Venezuela. The state capacity needed to monitor and deliver public goods has been further eroded by years of politicization, corruption and economic decline – a problem ignored by opposition politicians such as Juan Guaido, who has sought to re-engage former military officers currently in exile in various countries.

In line with the prescriptions of civilian-military researcher Peter D. Favor, Venezuela’s new leaders must re-establish objective civilian oversight and budgetary oversight as well as create civilian expertise through education and research centers. A civilian defense minister should be appointed and the number of senior officers reduced.

On the other hand, future civil-military relations in Venezuela must be constrained by the concept of discretion: first, establishing legal limits within which officers can choose; Second, provide “left-right” boundaries in military parlance where the officer has this authority. Doing so requires formal institutions and informal norms, as civil-military scholar Sam Sarkeesian has suggested. In terms of formal institutions, this means restricting the roles of military officers in issues related to defense and foreign policy, as well as giving civilians the right to decide what issues may be considered as such. It also means instilling values related to interaction with citizens, such as integrity, respect for human rights, and a willingness to work with subnational civilian political authorities to support state capacity.

The United States can assist Venezuela in this endeavor through personnel and institutional means, without becoming unduly involved in domestic politics. It can send researchers and practitioners to design new civil-military institutions, such as laws and regulations, and educate civilians on military-related matters. To help the Venezuelan military, it could fund a rapid revamp of the National Guard’s state partnership program. This program was created in the early 1990s to help develop democratic civil-military relations in post-Soviet countries. It has since evolved to train partner nations’ militaries to assist civilians in missions as diverse as counter-narcotics operations and natural disaster recovery efforts – all activities that increase state capacity.

The process of establishing truly democratic civil-military relations – not just a façade for them, as Venezuela once did – will require the consent of both civilian and military leaders. It will also take years of patient work, but it remains the only way to stability.

Don’t miss more hot News like this! Click here to discover the latest in Politics news!

2026-01-07 21:58:00