China Is Targeting Its Own Famous Artists

A Bangkok museum curator recently fled to London after Chinese and Thai officials pressured him to remove the names of Hong Kong, Uighur and Tibetan artists from an exhibition. They included artists Clara Cheung and Geum Cheng Yi Man, who created an installation about espionage and whose names were removed from the show, which was critical of authoritarian governments. These pressures were just one example of the Chinese Communist Party’s growing campaign to crack down on dissident artists and ensure that only government-approved messages appear in galleries, both inside and outside China’s borders.

The pressure exerted by Chinese officials in Thailand follows the arrest in January of Christian musician and performance artist Fei Xiaosheng, a resident of the Songzhuang arts district in eastern Beijing. Fai’s friends believe the authorities targeted him because of his public solidarity with Hong Kong’s democracy movement. For decades, Fei has used symbolism in his installations to criticize the Chinese Communist Party, including, in a 2011 photography exhibition, a blank wall display in honor of the then-detained artist Ai Weiwei. Before President Xi Jinping took power, artists like Fei tested the limits of political expression, leading to a thriving contemporary art scene in China. But the space for artistic independence is rapidly narrowing as authorities try to use art to impose a positive image of the Chinese Communist Party’s past.

A Bangkok museum curator recently fled to London after Chinese and Thai officials pressured him to remove the names of Hong Kong, Uighur and Tibetan artists from an exhibition. They included artists Clara Cheung and Geum Cheng Yi Man, who created an installation about espionage and whose names were removed from the show, which was critical of authoritarian governments. These pressures were just one example of the Chinese Communist Party’s growing campaign to crack down on dissident artists and ensure that only government-approved messages appear in galleries, both inside and outside China’s borders.

The pressure exerted by Chinese officials in Thailand follows the arrest in January of Christian musician and performance artist Fei Xiaosheng, a resident of the Songzhuang arts district in eastern Beijing. Fai’s friends believe the authorities targeted him because of his public solidarity with Hong Kong’s democracy movement. For decades, Fei has used symbolism in his installations to criticize the Chinese Communist Party, including, in a 2011 photography exhibition, a blank wall display in honor of the then-detained artist Ai Weiwei. Before President Xi Jinping took power, artists like Fei tested the limits of political expression, leading to a thriving contemporary art scene in China. But the space for artistic independence is rapidly narrowing as authorities try to use art to impose a positive image of the Chinese Communist Party’s past.

Visitors view a piece by Chinese artist Ai Weiwei Han Dynasty Drop Urn At an exhibition in Bologna, Italy, on September 20, 2024.Roberto Serra/Iguana Press via Getty Images

Fei’s arrest came a few months after the arrest of another prominent artist, Gao Chen. Gao Chen, a permanent resident of the United States, was visiting China when police arrested him at his studio outside Beijing in front of his wife and child, who were traveling with him, on August 26, 2024. Authorities said they detained him on suspicion of insulting the heroes and martyrs of the revolution.

“Our works represent a critique of tyranny and a call for historical reflection, but they are not works of slander,” said Li Gaoqiang, Gao Chen’s brother and artistic partner.

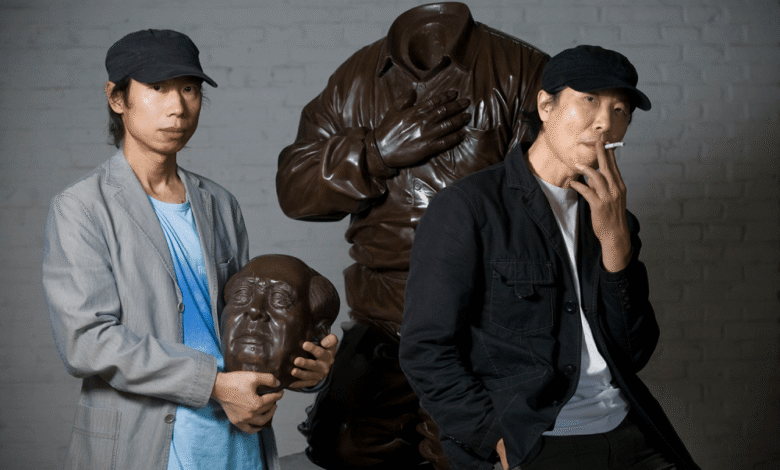

In 2011, I made a documentary about the Gao brothers and the Songzhuang Art District. The duo created provocative pieces depicting leaders such as Mao, Lenin, Stalin, Hitler and bin Laden. Gao Qiang said their work was an exploration of “the myths surrounding authoritarian figures and the damage caused by their unchecked power.” At the time, Beijing gave the Gao brothers some freedom, allowing politically sensitive artworks to remain standing, covered with canvas, in the back of their studio.

The Zhao brothers’ work has been sold to American movie stars and business tycoons, such as Leonardo DiCaprio and hedge fund tycoon Steve Cohen, and they have shown their work in galleries around the world. I photographed a Beijing studio where workers were preparing artworks to be shipped overseas, including a bronze sculpture titled “Mao’s Guilt,” which depicts the Chinese leader on his knees, contrite and pleading. I watched workers separate the statue into parts, keep Mao Zedong’s head and body in individual boxes, and partially obscure its icon from the Chinese customs authority, which approves the export of all works of art.

Under Xi, the party has become more sensitive to historical memory. China’s “Heroes and Martyrs” law, first introduced in 2018, attempts to force history into the Chinese Communist Party’s preferred narratives. Formal criminal penalties were added in 2021, as part of the newly amended Criminal Code. The law seeks to “inspire glorious spiritual power to realize China’s dream of the great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation”; It calls on society to “respect, learn from and defend national heroes”; Defaming them is criminalized with sentences of up to three years in prison. Its attempt to create a unified national memory precludes artistic expression and interpretations that challenge the authority of the Chinese Communist Party. The government established phone hotlines and apps for citizens to report violations of the law to authorities, and those arrested included a blogger, a journalist, and citizens who only posted on social media.

Gao Qiang says the artworks being investigated by the Chinese government were created more than 10 years ago, before the law was passed, and that authorities are using his brother’s arrest to send a “chilling message to others: Stay in line or face the consequences.” The authorities confiscated more than 100 of their artworks. The investigation focuses on a few pieces in particular: the “Mao’s Guilt” statue; “The Execution of Christ,” which features six life-size bronze statues of Mao pointing spears at a statue of Jesus Christ; and the “Miss Mao” series, which depicts the Chinese leader with an elongated nose and breasts.

Beijing uses this law to suppress the work of artists in China, and expands its scope to put pressure on those who have fled, seeking refuge in free and democratic countries. Gu Jian, an artist living in Australia, has seen his artwork removed from galleries and displays, and has been tempted to only display paintings that meet the party’s preferred standards.

A modern art dealer shows a customer a painting by Li Feng at Panjiayuan Market in Beijing on November 10, 2022. Mark Ralston/South China Morning Post via Getty Images

Guo Jian began his career as a propaganda artist in the People’s Liberation Army. In 1989, he joined the protests in Tiananmen Square and became an advocate for democracy. He began drawing satirical takes on Cultural Revolution iconography, using, he told me, “jokes to poke holes in Chinese propaganda narratives.” Guo Jian made Lei Feng, a heroic soldier in the People’s Liberation Army, the subject of many of his paintings. Li Feng appeared in several important propaganda campaigns in the 1960s, exemplifying selfless service and devotion to Mao Zedong. The Chinese Communist Party is now reviving Li Feng’s stories to promote them through Chinese state media. In 2023, Xinhua News Agency quoted a hydropower plant worker who prevented villages from flooding as saying: “Times are changing, but we still need Lei Feng’s spirit. The things he did may seem trivial, but behind them there was a nobility that we can all achieve.”

Guo Jian’s subversive paintings depict Lei Feng differently, such as on the cover of a magazine Playboy magazine. “Political propaganda makes figures like Li Feng cover stars of reputable publications like Photography of the people and People’s Liberation Army’s photoThey are as popular as the models on the cover of the magazine Playboy magazine. “The difference is that one post is considered inappropriate while the other is considered falsely serious or dangerous,” Guo Jian told me. He said the paintings are also a reflection of the readers of advertising and publicity. Playboy Magazine as a “passive audience” and uncritical, non-negotiable “objects of consumption.”

Regarding the threats he faced in Australia from the Chinese Communist Party and the removal of his paintings from some Australian galleries, Guo Jian said: “When I was in China, [working] As a publicist, I knew this kind of strategy. This is a tactic of separation and isolation, and it is also changing you, changing the entire map of the art world to show to the world.

Guo Jian and I were friends for many years in China, and in 2014 I photographed his studio in Beijing. Over time, I watched his anger at the CCP authorities grow, and when I visited his home that same year, Guo Jian showed me a diorama he had made of Tiananmen Square. He depicted the square as being surrounded by bulldozers, a symbol of China’s land grabs, and covered it with ground red meat, commemorating the brutality it witnessed during the 1989 protests. I knew, when I saw the diorama, that Gu Jian would face the consequences. Chinese government authorities quickly arrested him for showing this to me and another journalist, and within weeks deported Guo Jian to Australia, where he held her citizenship.

Now Gao Chen faces even more dire consequences for art that tells a story of China’s past that differs from the official and approved narratives of the Chinese Communist Party. Gao Chen’s family expects his trial to begin later this year, and fears a coercive sentence. The authorities imposed a ban on the exit of his wife and 7-year-old son, and prevented them from returning to their home in the United States. His brother Gao Qiang said their wealth and fame provide no protection in China.

Artist Casey Wong plays the accordion inside a mobile red prison artwork called Nationala protest performance art project, at an art studio in Hong Kong on December 6, 2018.Anthony Wallace/AFP via Getty Images.

As the government promotes art that mobilizes devotion to party-chosen heroes, Gao Qiang predicts that control over China’s art world will tighten, limiting “historical reflection and freedom of expression, and strengthening the CCP’s ideological grip, but perhaps at the expense of cultural and intellectual vitality.” He said the consequences extend beyond the artists whom Beijing persecutes to create a climate of fear throughout society, stifling critical discourse and innovation.

The Chinese Communist Party’s Law on the Protection of “Heroes and Martyrs” states that it aims to “preserve societal public interest” and inspire patriotism. But through its heavy-handed attempts to construct a dominant narrative of its past, Beijing is damaging its credibility and potentially jeopardizing its future.

Don’t miss more hot News like this! Click here to discover the latest in Politics news!

2025-10-31 18:00:00