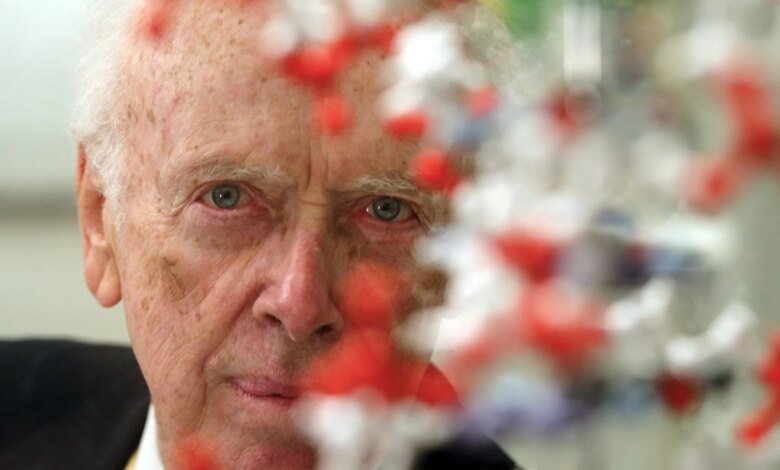

James Watson, who co-discovered the DNA double helix when he was 24 years old, dies at 97

James D. died. Watson, whose joint discovery of the twisted ladder structure of DNA in 1953 helped spark a long revolution in medicine, crime control, genealogy and ethics. He was 97 years old.

The feat—achieved when Chicago-born Watson was just 24 years old—turned him into a cult figure in the world of science for decades. But near the end of his life, he faced condemnation and professional censure for making offensive statements, including saying that blacks were less intelligent than whites.

Watson shared the 1962 Nobel Prize with Francis Crick and Maurice Wilkins for their discovery that deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) is a double helix, consisting of two strands that wrap around each other to form something like a long, gently twisted ladder.

This realization was a breakthrough. He immediately suggested how genetic information is stored and how cells replicate their DNA when they divide. The process of replication begins with the two strands of DNA being separated from each other like a zipper.

Even among non-scientists, the double helix would become an instantly recognizable symbol of science, appearing in places such as works by Salvador Dali and the British postage stamp.

This discovery helped open the door to more modern developments such as modifying the genetic makeup of organisms, treating diseases by inserting genes into patients, identifying human remains and criminal suspects from DNA samples, and tracing family trees and ancient human ancestors. But it also raises a host of ethical questions, such as whether we should change body plans for cosmetic reasons or in a way that is passed on to a person’s offspring.

“Francis Crick and I made the discovery of the century, and it was very clear,” Watson once said. “We could not have predicted the explosive impact of the double helix on science and society,” he later wrote.

Watson has never created another laboratory of this size. But in the decades since, he has written influential textbooks and best-selling memoirs, and helped direct the project to map the human genome. He selected bright young scholars and helped them. He used his prestige and connections to influence scientific policy.

Watson died in a nursing home after a brief illness, his son said Friday. His former research laboratory confirmed that he had died the previous day.

“He never stopped fighting for people with the disease,” Duncan Watson said of his father.

Watson’s initial motivation for supporting the Gene Project was personal: his son Rufus had been hospitalized with a possible diagnosis of schizophrenia, and Watson believed that knowing the full makeup of DNA would be crucial to understanding this disease—perhaps in time to help his son.

He gained unwelcome attention in 2007, when he was quoted in London’s Sunday Times Magazine as saying he was “inherently gloomy about Africa’s prospects” because “all our social policies depend on the fact that their intelligence is the same as ours – which all tests indicate is not true.” While he hopes everyone is equal, “people who have to deal with black employees find that’s not true,” he said.

He apologized, but after an international uproar he was suspended from his job as a consultant to the prestigious Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory in New York. He retired a week later. He has served in various leadership capacities there for nearly 40 years.

In a television documentary broadcast in early 2019, Watson was asked if his views had changed. “No, not at all,” he said. In response, Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory rescinded several honorary titles it had bestowed on Watson, saying his statements were “reprehensible” and “not supported by science.”

Watson’s combination of scientific achievement and controversial observations created a complex legacy.

He showed “an unfortunate tendency toward inflammatory and offensive comments, especially late in his career,” Dr. Francis Collins, then director of the National Institutes of Health, said in 2019. His outbursts of anger, especially when reflected on race, were extremely misguided and extremely hurtful. “I only hope Jim’s views on society and humanity match his brilliant scientific ideas.”

Long before that, Watson despised political correctness.

“A fair number of scientists are not only narrow-minded and boring, they are also stupid,” he wrote in The Double Helix, his 1968 best-seller about the discovery of DNA.

To achieve success in science, he wrote: “You must avoid stupid things. … Never do anything that bores you. … If you cannot be with your real peers (including scientific competitors) then get out of science. … To achieve great success, a scientist must be prepared to get into deep trouble.”

It was the fall of 1951, and Watson was tall, lean, and already had a Ph.D. At the age of twenty-three, he arrived at the British University of Cambridge, where he met Crick. As Watson’s biographer later put it: “It was intellectual love at first sight.”

Crick himself wrote that the partnership flourished in part because the two men shared “a kind of youthful arrogance, cruelty, and impatience with sloppy thinking.”

Together they sought to manipulate the structure of DNA, aided by X-ray research by colleague Rosalind Franklin and graduate student Raymond Gosling. Watson was later criticized for her disparaging portrayal of Franklin in “The Double Helix,” and today she is considered a prominent example of a female scientist whose contributions have been overlooked. (She died in 1958).

Watson and Crick built Tinker’s toy-like models to determine the structure of the molecule. One Saturday morning in 1953, after fiddling with pieces of cardboard that he had carefully cut to represent parts of the DNA molecule, Watson suddenly realized how these pieces could form the “rungs” of a double-helical staircase.

His first reaction: “She’s so beautiful.”

Bruce Stillman, president of Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, said the discovery of the double helix “is one of the three most important discoveries in the history of biology,” along with Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution by natural selection and Gregor Mendel’s fundamental laws of genetics.

After this discovery, Watson spent two years at the California Institute of Technology, then joined the Harvard faculty in 1955. Before leaving Harvard in 1976, he established the university’s molecular biology program, scientist Mark Ptashny recalled in a 1999 interview.

Watson became director of Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory in 1968, president in 1994, and chancellor 10 years later. He made the laboratory on Long Island an educational center for scientists and non-scientists, focused research on cancer, instilled excitement and raised huge sums of money.

Ptashny said he had transformed the laboratory into a “vibrant and very important center.” She was “one of Jim’s miracles: a shaggier, less smooth, less flattering person you could ever imagine.”

From 1988 to 1992, Watson directed federal efforts to determine the detailed structure of human DNA. He created the project’s huge investment in ethics research by simply announcing it at a press conference. He later said that this was “probably the wisest thing I’ve done over the past decade.”

Watson was present at the White House in 2000 to announce that the federal project had accomplished an important goal: a “working draft” of the human genome, essentially a road map for an estimated 90 percent of human genes.

Researchers provided Watson with a detailed description of its genome in 2007. It was one of the first genomes of an individual to be decoded.

Watson knew that genetic research could produce results that make some people uncomfortable. In 2007, he wrote that when scientists identify genetic variants that make people vulnerable to crime or significantly affect intelligence, the results should be published rather than suppressed outside the context of political correctness.

James Dewey Watson was born in Chicago on April 6, 1928, into “a family that believed in books, birds and the Democratic Party,” as he put it. From his bird-watching father, he inherited an interest in ornithology and an aversion to explanations not based on reason or science.

Watson was a precocious child who loved to read and study books such as The World Telegraph Almanac. He entered the University of Chicago on a scholarship at the age of fifteen, graduated at nineteen and received his doctorate in zoology from Indiana University three years later.

He became interested in genetics when he was 17 when he read a book that said genes were the essence of life.

“I thought: ‘Well, if the gene is what life is, I want to know more about it,'” he later recalled. “That was fateful, because otherwise I would have spent my life studying birds and no one would have heard of me.”

At that time, it was not clear that genes were made of DNA, at least for any life form other than bacteria. But Watson went to Europe to study the biochemistry of nucleic acids such as DNA. At a conference in Italy, Watson saw an X-ray image indicating that DNA could form crystals.

“Suddenly I became excited about chemistry,” Watson wrote in his book The Double Helix. If genes are to be crystallized, “they must have a regular structure that can be solved in a straightforward manner.”

“It was impossible to get the potential key to the secret of life out of my mind,” he recalls.

In the decades following his discovery, Watson’s fame continued. Apple Computer used his image in an advertising campaign. At conferences, graduate students who weren’t even born when he was working at Cambridge would nudge each other and whisper: “There’s a Watson. There’s a Watson.” They had him sign napkins or copies of “The Double Helix.”

A reporter asked him in 2018 if any building at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory bore his name. No, Watson replied, “I don’t need a building named after me. I have the Double Helix.”

His comments about race in 2007 were not the first time Watson had struck a chord with his comments. In a speech in 2000, he suggested that sexual drive is linked to skin color. He had previously told a newspaper that if the gene that regulates sexuality is found to be detectable in the womb, a woman who does not want to have a gay child should be allowed to have an abortion.

More than half a century after winning the Nobel Prize, Watson put the gold medal up for auction in 2014. The winning bid, $4.7 million, set a record for a Nobel Prize. The medal was eventually returned to Watson.

Both Watson’s Nobel Prize winners, Crick and Wilkins, died in 2004.

___

Ritter is a retired AP science writer. AP Science Writers Christina Larson in Washington and Adithi Ramakrishnan in New York contributed to this report.

___

The Associated Press Health and Science Department receives support from the Howard Hughes Medical Institute’s Department of Science Education and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. AP is solely responsible for all content.

Don’t miss more hot News like this! Click here to discover the latest in Business news!

2025-11-09 16:16:00