Chainsaw Man’s Creator Wrote A Found Footage Movie… As A Comic Book

We may receive a commission for purchases made from our links.

Tatsuki Fujimoto, the creator of “Chainsaw Man,” loves movies and brings that love to his comics. Makima, the terrifying antagonist of Chainsaw Man, shares her creator’s passion for cinema. One chapter, which was adapted into the recent “Chainsaw Man: The Movie — Reze Arc,” sees Makima bringing our hero Denji on a movie marathon date. The “Reze Arc” itself is Fujimoto exploring the conventions of rom-coms and romantic comedies, then brutally twisting them. At the climax of Chainsaw Man Part 1, Makima explains that she just wants to cleanse the world of its ills – including bad movies.

In Fujimoto’s first serialized manga, the web series Fire Punch, revenge-seeking hero Agni obtains a togata. Togata, obsessed with cinema, wants to depict Agni’s revenge and is not above manipulating others to provide the best “scenes.” Fujimoto revisits the docuseries in 2022’s “Goodbye, Eri” one-shot, which was released between Parts 1 and 2 of “Chainsaw Man.” The 200-page comic is framed through the lens of a cell phone camera—a comedic “snapshot” like a found footage film. However, “Goodbye Eri” is one of Fujimoto’s only works (along with “Fire Punch”) that has not yet been adapted into an anime, although its formal gimmicks are all taken from the cinema.

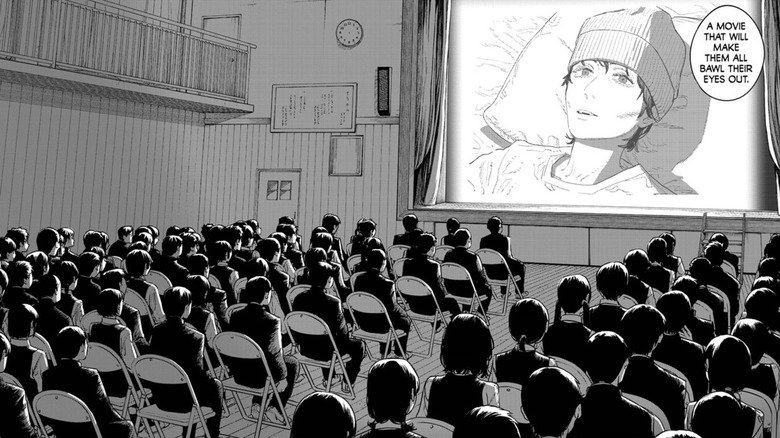

“Goodbye, Eri” is about a young Japanese boy named Yuta, who, at the request of his terminally ill mother, films her dying days. The first 20 pages of the skit were shown like this, before it was revealed that the panels we were seeing were from Yuuta’s final film, which is shown to his classmates and then criticized (because he chose to end the film running from an explosion). Everyone hates Yuuta’s “insensitive” movie… except for a girl named Eri, who decides to teach Yuuta how to make a better movie by having him watch dozens of movies with her. The comic follows Yuta as he envisions his days with Eri, which may also be numbered.

Fujimoto explores the power of movies in Goodbye, Eri

“Goodbye, Eri” hits similar emotional (and meta-textual) tones to films like “Me, Earl, and the Dying Girl,” also about a teenage boy photographing someone’s final days, and Steven Spielberg’s semi-autobiographical “The Fabelmans.” “Goodbye, Eri” Fujimoto looks inward to explore what drives him as an artist and why he is fascinated by films. In this way, the film intersects with one of his other feature films, “Look Back,” which is about two girls with a shared passion for drawing manga art. “Look Back” was Fujimoto asking him why he painted, while “Goodbye, Eri” was him asking why someone would paint the world and its people.

The comic concludes that someone will do it He wants To be photographed because it offers immortality and shapes how a person is remembered. Found footage is somewhat synonymous with horror films and not just because the grungy camera lends itself to a nightmarish atmosphere. Found footage horror films offer a supposed look at the “real” last moments of the person filming the footage. What’s more disturbing to watch than that?

They may be shot like documentaries, but found footage films are of course sincerely fictional, offering only the aesthetic of reality. In “Goodbye, Eri,” Yuta always feels compelled to bring “a little bit of imagination” to his films. As for the movie he makes after Eri, he depicts her as not just a sick girl but a 1,200-year-old vampire. This, of course, reflects Fujimoto’s addition of “a little imagination.” He’s the one who tells us the story of Yuta and Eri, the same story Yuta makes into his next film, and Fujimoto throws the possibility of vampirism (reflecting how people never die if depicted in film) into what is otherwise a slice-of-life premise.

Goodbye, Eri slices reality and finds snapshots

Found footage exploded in popularity in the early 2000s, when digital film and cameras became the norm. Cell phones, with their built-in cameras and microphones, are now as ubiquitous a tool as paper and pencil. In theory, it’s as easy to make a movie as it is to draw storyboards. In “Goodbye, Eri,” Fujimoto does the latter to tell a story about doing the former. However, the cell phone framing of “Goodbye, Eri” is never a gimmick.

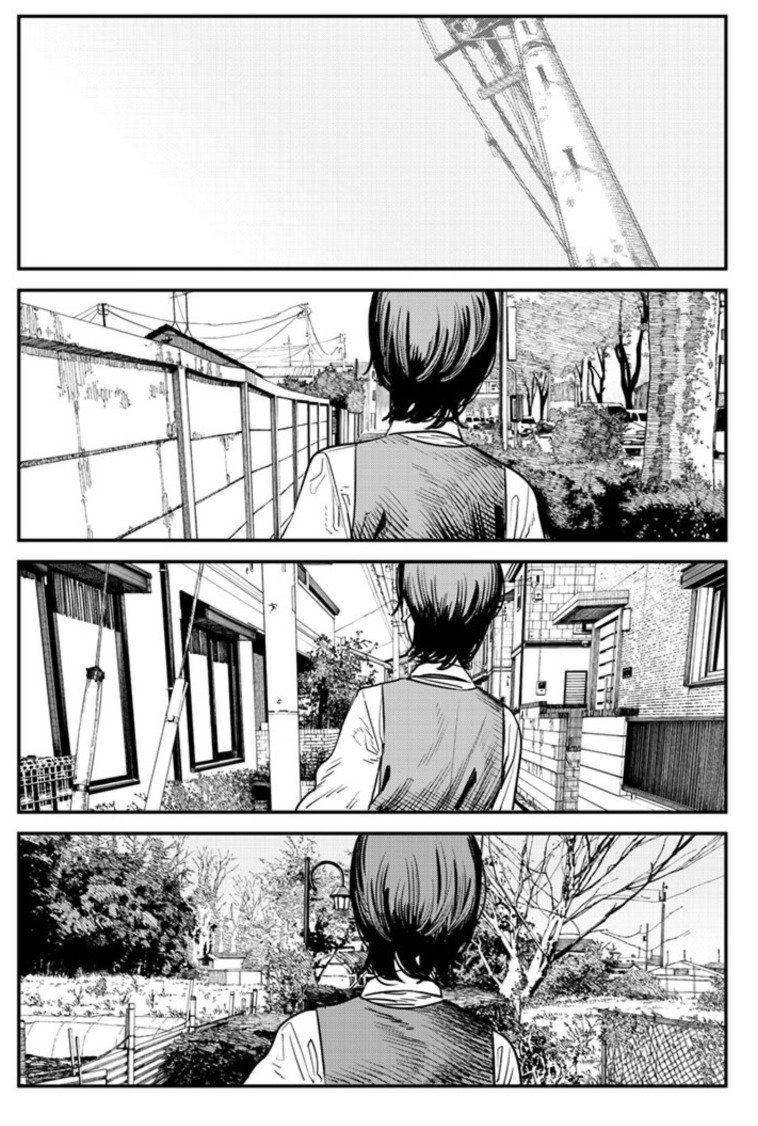

Most of the pages of “Goodbye Erie” use four long rectangular panels, suggesting the uniform, boxy look of a cell phone screen. The jumps in time and space between these panels range from minimal (take the multiple pages to Yuta and Eri sitting on the couch together watching movies) to massive.

The opening pages depicting Yuta’s film about his mother use a single panel of a single shot from the film, suggesting cinematic montage editing. However, the decompressed pages of “Goodbye, Erie” convey the feeling of looking into a cell phone camera and the image does not change.

Many of the panels in “Goodbye, Eri” are intentionally painted with blur, to suggest that the fictional cell phone depicting the frame is moving. Since Yuta films everything, and this is the (literal) lens through which we see the story, the pages rarely begin with a clear indication of what is real and what is staged. A comic is able to create transitions within a scene more easily than any film.

As for the theme of Yuuta’s film, Eri fits in with Fujimoto’s other characters like Rize and Makima; A woman with hypnotic eyes looks innocent and not at the same time. A good film needs something or someone compelling to follow it, and Airy passes that test.

Don’t miss more hot News like this! Click here to discover the latest in Entertainment news!

2026-01-06 01:45:00