Freddy the Robot and the Great Debate over AI’s Future

Meet

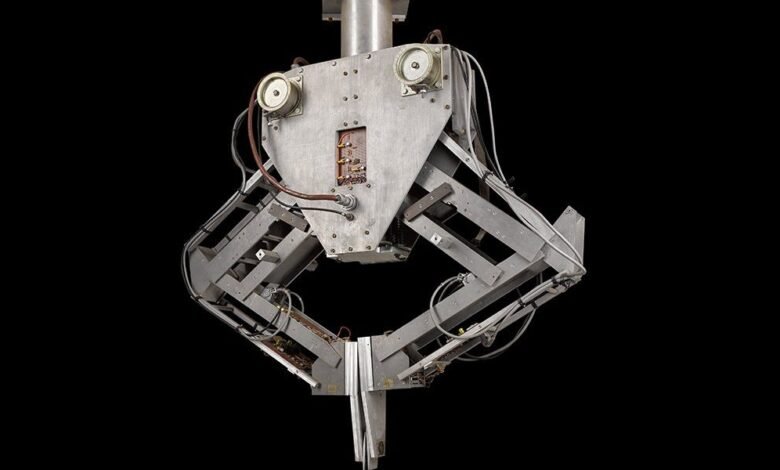

FREDERICK Mark 2, the Friendly Robot for Education, Discussion and Entertainment, the Retrieval of Information, and the Collation of Knowledge, better known as Freddy II. This remarkable robot could put together a simple model car from an assortment of parts dumped in its workspace. Its video-camera eyes and pincer hand identified and sorted the individual pieces before assembling the desired end product. But onlookers had to be patient. Assembly took about 16 hours, and that was after a day or two of “learning” and programming.

Freddy II was completed in 1973 as one of a series of research robots developed by Donald Michie and his team at the University of Edinburgh during the 1960s and ’70s. The robots became the focus of an intense debate over the future of AI in the United Kingdom. Michie eventually lost, his funding was gutted, and the ensuing AI winter set back U.K. research in the field for a decade.

Why were the Freddy I and II robots built?

In 1967,

Donald Michie, along with Richard Gregory and Hugh Christopher Longuet-Higgins, founded the Department of Machine Intelligence and Perception at the University of Edinburgh with the near-term goal of developing a semiautomated robot and then longer-term vision of programming “integrated cognitive systems,” or what other people might call intelligent robots. At the time, the U.S. Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency and Japan’s Computer Usage Development Institute were both considering plans to create fully automated factories within a decade. The team at Edinburgh thought they should get in on the action too.

Two years later,

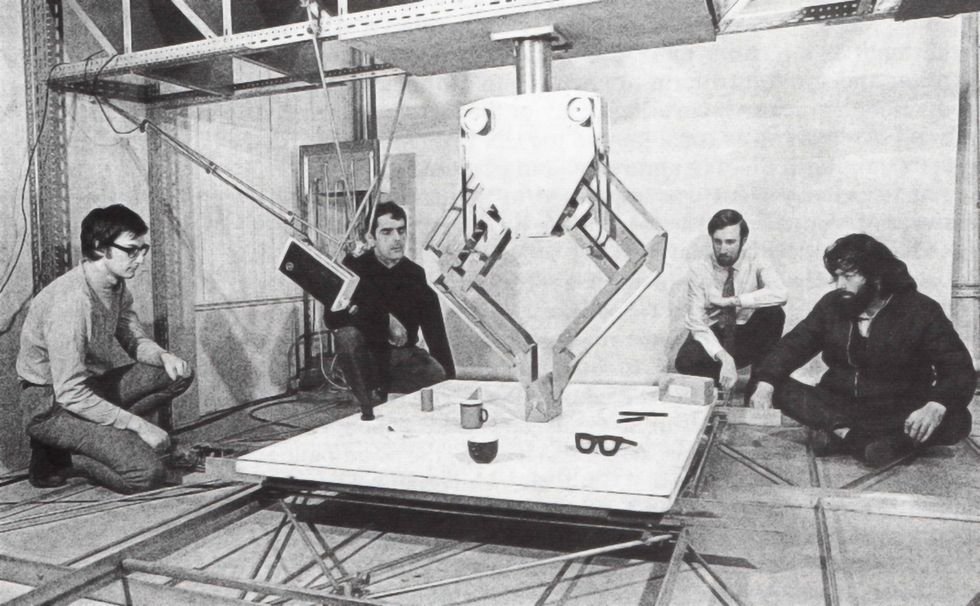

Stephen Salter and Harry G. Barrow joined Michie and got to work on Freddy I. Salter devised the hardware while Barrow designed and wrote the software and computer interfacing. The resulting simple robot worked, but it was crude. The AI researcher Jean Hayes (who would marry Michie in 1971) referred to this iteration of Freddy as an “arthritic Lady of Shalott.”

Freddy I consisted of a robotic arm, a camera, a set of wheels, and some bumpers to detect obstacles. Instead of roaming freely, it remained stationary while a small platform moved beneath it. Barrow developed an adaptable program that enabled Freddy I to recognize irregular objects. In 1969, Salter and Barrow published in

Machine Intelligence their results, “Design of Low-Cost Equipment for Cognitive Robot Research,” which included suggestions for the next iteration of the robot.

Freddy I, completed in 1969, could recognize objects placed in front of it—in this case, a teacup.University of Edinburgh

More people joined the team to build Freddy Mark 1.5, which they finished in May 1971. Freddy 1.5 was a true robotic hand-eye system. The hand consisted of two vertical, parallel plates that could grip an object and lift it off the platform. The eyes were two cameras: one looking directly down on the platform, and the other mounted obliquely on the truss that suspended the hand over the platform. Freddy 1.5’s world was a 2-meter by 2-meter square platform that moved in an

x–y plane.

Freddy 1.5 quickly morphed into Freddy II as the team continued to grow. Improvements included force transducers added to the “wrist” that could deduce the strength of the grip, the weight of the object held, and whether it had collided with an object. But what really set Freddy II apart was its versatile assembly program: The robot could be taught to recognize the shapes of various parts, and then after a day or two of programming, it could assemble simple models. The various steps can be seen in this extended video, narrated by Barrow:

The Lighthill Report Takes Down Freddy the Robot

And then what happened?

So much. But before I get into all that, let me just say that rarely do I, as a historian, have the luxury of having my subjects clearly articulate the aims of their projects, imagine the future, and then, years later, reflect on their experiences. As a cherry on top of this historian’s delight, the topic at hand—artificial intelligence—also happens to be of current interest to pretty much everyone.

As with many fascinating histories of technology, events turn on a healthy dose of professional bickering. In this case, the disputants were Michie and the applied mathematician

James Lighthill, who had drastically different ideas about the direction of robotics research. Lighthill favored applied research, while Michie was more interested in the theoretical and experimental possibilities. Their fight escalated quickly, became public with a televised debate on the BBC, and concluded with the demise of an entire research field in Britain.

A damning report in 1973 by applied mathematician James Lighthill [left] resulted in funding being pulled from the AI and robotics program led by Donald Michie [right]. Left: Chronicle/Alamy; Right: University of Edinburgh

A damning report in 1973 by applied mathematician James Lighthill [left] resulted in funding being pulled from the AI and robotics program led by Donald Michie [right]. Left: Chronicle/Alamy; Right: University of Edinburgh

It all started in September 1971, when the British Science Research Council, which distributed public funds for scientific research, commissioned Lighthill to survey the state of academic research in artificial intelligence. The SRC was finding it difficult to make informed funding decisions in AI, given the field’s complexity. It suspected that some AI researchers’ interests were too narrowly focused, while others might be outright charlatans. Lighthill was called in to give the SRC a road map.

No intellectual slouch, Lighthill was the Lucasian Professor of Mathematics at the University of Cambridge, a position also held by Isaac Newton, Charles Babbage, and Stephen Hawking. Lighthill solicited input from scholars in the field and completed his report in March 1972. Officially titled “

Artificial Intelligence: A General Survey,” but informally called the Lighthill Report, it divided AI into three broad categories: A, for advanced automation; B, for building robots, but also bridge activities between categories A and C; and C, for computer-based central nervous system research. Lighthill acknowledged some progress in categories A and C, as well as a few disappointments.

Lighthill viewed Category B, though, as a complete failure. “Progress in category B has been even slower and more discouraging,” he wrote, “tending to sap confidence in whether the field of research called AI has any true coherence.” For good measure, he added, “AI not only fails to take the first fence but ignores the rest of the steeplechase altogether.” So very British.

Lighthill concluded his report with his view of the next 25 years in AI. He predicted a “fission of the field of AI research,” with some tempered optimism for achievement in categories A and C but a valley of continued failures in category B. Success would come in fields with clear applications, he argued, but basic research was a lost cause.

The Science Research Council published Lighthill’s report the following year, with responses from

N. Stuart Sutherland of the University of Sussex and Roger M. Needham of the University of Cambridge, as well as Michie and his colleague Longuet-Higgins.

Sutherland sought to relabel category B as “basic research in AI” and to have the SRC increase funding for it. Needham mostly supported Lighthill’s conclusions and called for the elimination of the term AI—“a rather pernicious label to attach to a very mixed bunch of activities, and one could argue that the sooner we forget it the better.”

Longuet-Higgins focused on his own area of interest, cognitive science, and ended with an ominous warning that any spin-off of advanced automation would be “more likely to inflict multiple injuries on human society,” but he didn’t explain what those might be.

Michie, as the United Kingdom’s academic leader in robots and machine intelligence, understandably saw the Lighthill Report as a direct attack on his research agenda. With his funding at stake, he provided the most critical response, questioning the very foundation of the survey: Did Lighthill talk with any international experts? How did he overcome his own biases? Did he have any sources and references that others could check? He ended with a request for

more funding—specifically the purchase of a DEC System 10 (also known as the PDP-10) mainframe computer. According to Michie, if his plan were followed, Britain would be internationally competitive in AI by the end of the decade.

After Michie’s funding was cut, the many researchers affiliated with his bustling lab lost their jobs.University of Edinburgh

After Michie’s funding was cut, the many researchers affiliated with his bustling lab lost their jobs.University of Edinburgh

This whole affair might have remained an academic dispute, but then the BBC decided to include a debate between Lighthill and a panel of experts as part of its “Controversy” TV series. “Controversy” was an experiment to engage the public in science. On 9 May 1973, an interested but nonspecialist audience filled the auditorium at the Royal Institution in London to hear the debate.

Lighthill started with a review of his report, explaining the differences he saw between automation and what he called “the mirage” of general-purpose robots. Michie responded with a short film of Freddy II assembling a model, explaining how the robot processes information. Michie argued that AI is a subject with its own purposes, its own criteria, and its own professional standards.

After a brief back and forth between Lighthill and Michie, the show’s host turned to the other panelists:

John McCarthy, a professor of computer science at Stanford University, and Richard Gregory, a professor in the department of anatomy at the University of Bristol who had been Michie’s colleague at Edinburgh. McCarthy, who coined the term artificial intelligence in 1955, supported Michie’s position that AI should be its own area of research, not simply a bridge between automation and a robot that mimics a human brain. Gregory described how the work of Michie and McCarthy had influenced the field of psychology.

You can

watch the debate or read a transcript.

A Look Back at the Lighthill Report

Despite international support from the AI community, though, the SRC sided with Lighthill and gutted funding for AI and robotics; Michie had lost. Michie’s bustling lab went from being an international center of research to just Michie, a technician, and an administrative assistant. The loss ushered in the first British AI winter, with the United Kingdom making little progress in the field for a decade.

For his part, Michie pivoted and recovered. He decommissioned Freddy II in 1980, at which point it moved to the

Royal Museum of Scotland (now the National Museum of Scotland), and he replaced it with a Unimation PUMA robot.

In 1983, Michie founded the Turing Institute in Glasgow, an AI lab that worked with industry on both basic and applied research. The year before, he had written

Machine Intelligence and Related Topics: An Information Scientist’s Weekend Book (Gordon and Breach). Michie intended it as intellectual musings that he hoped scientists would read, perhaps on the weekend, to help them get beyond the pursuits of the workweek. The book is wide-ranging, covering his three decades of work.

In the introduction to the chapters covering Freddy and the aftermath of the Lighthill report, Michie wrote, perhaps with an eye toward history:

“Work of excellence by talented young people was stigmatised as bad science and the experiment killed in mid-trajectory. This destruction of a co-operative human mechanism and of the careful craft of many hands is elsewhere described as a mishap. But to speak plainly, it was an outrage. In some later time when the values and methods of science have further expanded, and those adversary politics have contracted, it will be seen as such.”

History has indeed rendered judgment on the debate and the Lighthill Report. In 2019, for example, computer scientist Maarten van Emden, a colleague of Michie’s,

reflected on the demise of the Freddy project with these choice words for Lighthill: “a pompous idiot who lent himself to produce a flaky report to serve as a blatantly inadequate cover for a hatchet job.”

And in a March 2024

post on GitHub, the blockchain entrepreneur Jeffrey Emanuel thoughtfully dissected Lighthill’s comments and the debate itself. Of Lighthill, he wrote, “I think we can all learn a very valuable lesson from this episode about the dangers of overconfidence and the importance of keeping an open mind. The fact that such a brilliant and learned person could be so confidently wrong about something so important should give us pause.”

Arguably, both Lighthill and Michie correctly predicted certain aspects of the AI future while failing to anticipate others. On the surface, the report and the debate could be described as simply about funding. But it was also more fundamentally about the role of academic research in shaping science and engineering and, by extension, society. Ideally, universities can support both applied research and more theoretical work. When funds are limited, though, choices are made. Lighthill chose applied automation as the future, leaving research in AI and machine intelligence in the cold.

It helps to take the long view. Over the decades, AI research has cycled through several periods of spring and winter, boom and bust. We’re currently in another AI boom. Is this time different? No one can be certain what lies just over the horizon, of course. That very uncertainty is, I think, the best argument for supporting people to experiment and conduct research into fundamental questions, so that they may help all of us to dream up the next big thing.

Part of a continuing series looking at historical artifacts that embrace the boundless potential of technology.

An abridged version of this article appears in the May 2025 print issue as “This Robot Was the Fall Guy for British AI.”

From Your Site Articles

Related Articles Around the Web

Don’t miss more hot News like this! Click here to discover the latest in AI news!

2025-04-30 14:00:00