Free the government’s hands by taking back its fiscal brain

Open Editor’s Digest for free

Rula Khalaf, editor of the Financial Times, picks her favorite stories in this weekly newsletter.

The writer is a contributing editor at the Financial Times and a former chief economist at the Bank of England

The Office for Budget Responsibility was set up by then Chancellor of the Exchequer George Osborne in 2010 to provide independent assessments of the UK’s public finances. It was rightly praised at the time for helping to depoliticize fiscal policy analysis – emulating the independent fiscal policy councils that operate successfully in a range of other countries.

Except in one respect. The Office for Budget Responsibility is charged with responsibility for macroeconomic forecasts and assessing the impact of fiscal measures. But unlike elsewhere, these functions have been transferred from the Ministry of Finance to the Office for Budget Responsibility, along with a great deal of in-house expertise that produces them. In one fell swoop, the Treasury’s role and expertise in macro matters was outsourced.

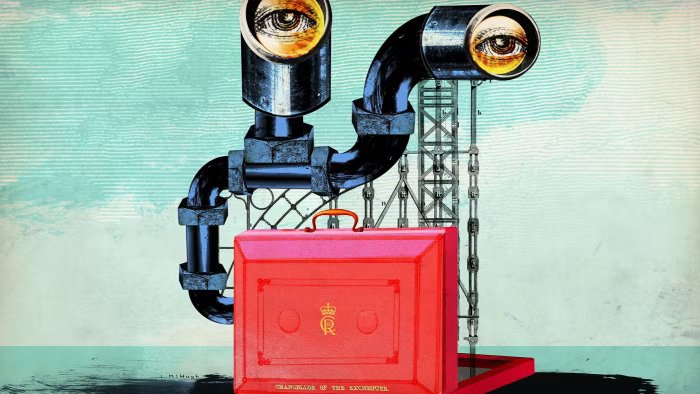

This institutional configuration means that while fiscal councils in other countries largely provide a “second pair of eyes”, the UK’s Office for Budget Responsibility has de facto monopoly rights over debt sustainability rulings – it is prosecutor, judge and jury. As the fiscal and growth outlook grows bleaker, the consequences are becoming increasingly alarming, both economically and politically.

Since 2010, fiscal policy has involved a careful balancing of measures to stimulate growth and maintain fiscal discipline. The mandate of the Office for Budget Responsibility covers only the second point. Its recording of financial measures decisively directs the institutional balance towards sustaining growth. Or rather, it has long since reinforced the Treasury’s first fiscal instincts. A cynic might imagine that this was the hidden motive behind Osborne’s “austerity”.

In the absence of an institutional sponsor, public investment and growth have been the victims. After years of underinvestment, the UK’s public sector capital stock is estimated to be around £2 trillion lower than its international counterparts in 2019, a gap that is almost certainly larger now. It is no coincidence that growth has stopped. An ill-mannered series of anemic growth plans has been accompanied by growing political unease with conservatism in the Office of Budget Management. This culminated in Liz Truss’s decision to sideline the Office for Budget Responsibility in preparations for the fateful 2022 “mini” Budget.

The resulting bond market collapse led current Chancellor Rachel Reeves to link OBR assessments to financial events, making the monopoly de facto de jure. Buyer’s remorse was quick. With poor prospects and very little room for financial manoeuvre, Reeves finds herself stuck in the pods of the Office for Budget Responsibility. It is on her educated guesses – and this is inevitably the case – that the fortunes of the Chancellor, the economy and tens of millions of taxpayers now depend.

This is neither an economically sensible nor a politically sustainable system of macroeconomic management. Nigel Farage, whose Reform UK party leads comfortably in the opinion polls, suggests that weak growth is the fault of the Office for Budget Responsibility. This is a mistake: it performs (perhaps too well) the task assigned to it. But he is right when he says that the financial system in which he is involved poses a problem not only for growth, but also for governance.

There is increasing recognition of this fact even in government. Reeves proposed reducing the number of OBR evaluations from two to one per year. This would somewhat reduce the uncertainty surrounding fiscal policy – a significant headwind to growth recently – but would not address the inherent inflexibility of the financial system.

One way to free up the government’s fiscal hands is to partially regain control of fiscal assessments. Outsourcing your mind is rarely wise. Like the Bank of England regarding monetary policy, the Treasury must produce and publish its economic forecasts and assessments of fiscal options. The role of the Office for Budget Responsibility, as in other countries, is to review these assessments.

Although the Treasury is no longer strictly constrained by the conservatism of the Office for Budget Responsibility, the institutional balance will tilt towards growth while maintaining independent scrutiny. Increasing transparency around financial choices improves public debate. But as the Bank’s experience shows, it would also provide strong incentives to improve the Treasury’s macroeconomic expertise and analysis, which has been wrongly damaged.

Besides, the fiscal framework itself needs to be rebalanced towards growth. In other areas of public policy with a high degree of uncertainty and where targets are trade-offs, such as inflation targeting, flexibility is provided by tolerance bands (within which there is no assumption that corrective action is needed) and lengthening the horizon over which targets are assessed. Fiscal policy needs both.

A tolerance band of 1 percent of GDP on fiscal rules would remove the need for growth-limiting pressure to promote fiscal headroom. On the other hand, a longer assessment horizon of these rules, beyond a single parliament, would allow the full fruits of growth-supporting investments to register, as they should, towards sustainability assessments.

In last year’s budget, the government switched to a broader measure of public debt while recognizing financial assets. This was wise, as it allowed for an additional investment of £20 billion a year over five years in housing, transport and energy. A better step would be to explicitly recognize non-financial assets in the definition of debt. Changing this rule could enable an additional £20 billion a year in tax-free growth and public investment.

Any change in the financial framework will not be without cost, especially in light of the fragility of the markets. But what ultimately matters to markets is the framework capable of delivering the great savior of debt: growth. The current framework is an obstacle. Countries with the financial flexibility to invest have higher growth and lower bond yields. In the next budget, this award will fall within the Chancellor’s reach.

2025-10-18 04:00:00