Iran’s New Moral Order Has Weakened the Islamic Regime

Iran is undergoing a profound transformation: one not of institutions or leadership, but of meaning. The Islamic republic continues to project strength through its security services and regional networks, yet it no longer controls the symbolic universe that once anchored its legitimacy.

In the last 15 years, Iranians have quietly constructed an alternative moral order rooted not in revolutionary sacrifice but in dignity, bodily autonomy, and truth-telling, including about the victims of the state. This bottom-up civil religion now challenges the core of the Islamic republic’s political theology more effectively than any party or organized opposition.

The shift did not happen overnight. It was built through a sequence of shocks that accumulated over time: the killing of Neda Agha-Soltan during the Green Movement protests in 2009, which transformed a protester into an unsanctioned national martyr; the mass killings during the nationwide economic protests of 2019; the execution of wrestler Navid Afkari in 2020, which underscored the regime’s indifference to public and international outrage; and the death of Mahsa Amini in police custody in 2022.

Each episode widened the gap between the regime’s sacred order and Iranian society. By the time protests erupted after Amini’s death, the state had lost the emotional authority to define who counts as a martyr, what is sacred, and what moral language could unify the nation.

The symbolic rupture has not receded, and this revolt of meaning is now one of the most consequential political developments in Iran. It has not toppled the Islamic republic and may not anytime soon, but it has reoriented the moral center of Iranian society in ways that will shape the country’s political future.

A supporter of defeated Iranian presidential candidate Mir-Hossein Mousavi shouts during protests in Tehran on June 13, 2009. Olivier Laban-Mattei/AFP via Getty Images

After the 1979 revolution, Iran’s rulers built their authority and governed through a powerful political theology that fused Shia martyrology, revolutionary mythmaking, and the memory of the Iran-Iraq War. The proverbial young martyr who gave his blood for the revolution became the state’s central icon. His image—haloed, pure, eternally youthful—filled murals, textbooks, and public squares. In this symbolic economy, the state defined the sacred, and society internalized it.

But the credibility of this system eroded, beginning in the late 1990s and accelerating in the 2000s. Corruption, inequality, and the widening gap between the revolutionary elite and ordinary Iranians made the state’s exalted moral language ring hollow. A younger generation with no memory of the war with Iraq, not to mention the Iranian Revolution, increasingly rejected the idea that sacrifice for the republic was a moral duty.

The rupture became visible in 2009, when millions of people took to the streets after a disputed presidential election. Iran’s security apparatus—namely the Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps (IRGC) and the paramilitary Basij—relied on familiar methods of repression. But it could not control the symbolic fallout after the killing of Agha-Soltan, captured on a cellphone camera and spread instantly around the world. Within hours, protesters declared her the “martyr of freedom,” and she became a national symbol unsanctioned by the state. The regime’s monopoly on defining sanctity cracked.

This struggle over meaning intensified over the next decade. During nationwide protests in November 2019, security forces killed hundreds of people, many from poor and marginalized communities. Their families refused silence: Mothers recorded videos demanding justice for their children, and their grief resonated beyond provincial towns. A year later, the execution of Afkari, a wrestler widely believed to have been tortured into confessing to the murder of a security guard during 2018 protests, produced another martyr whose words—“If I am executed, I want you to know that an innocent person … was executed”—circulated like a national lament.

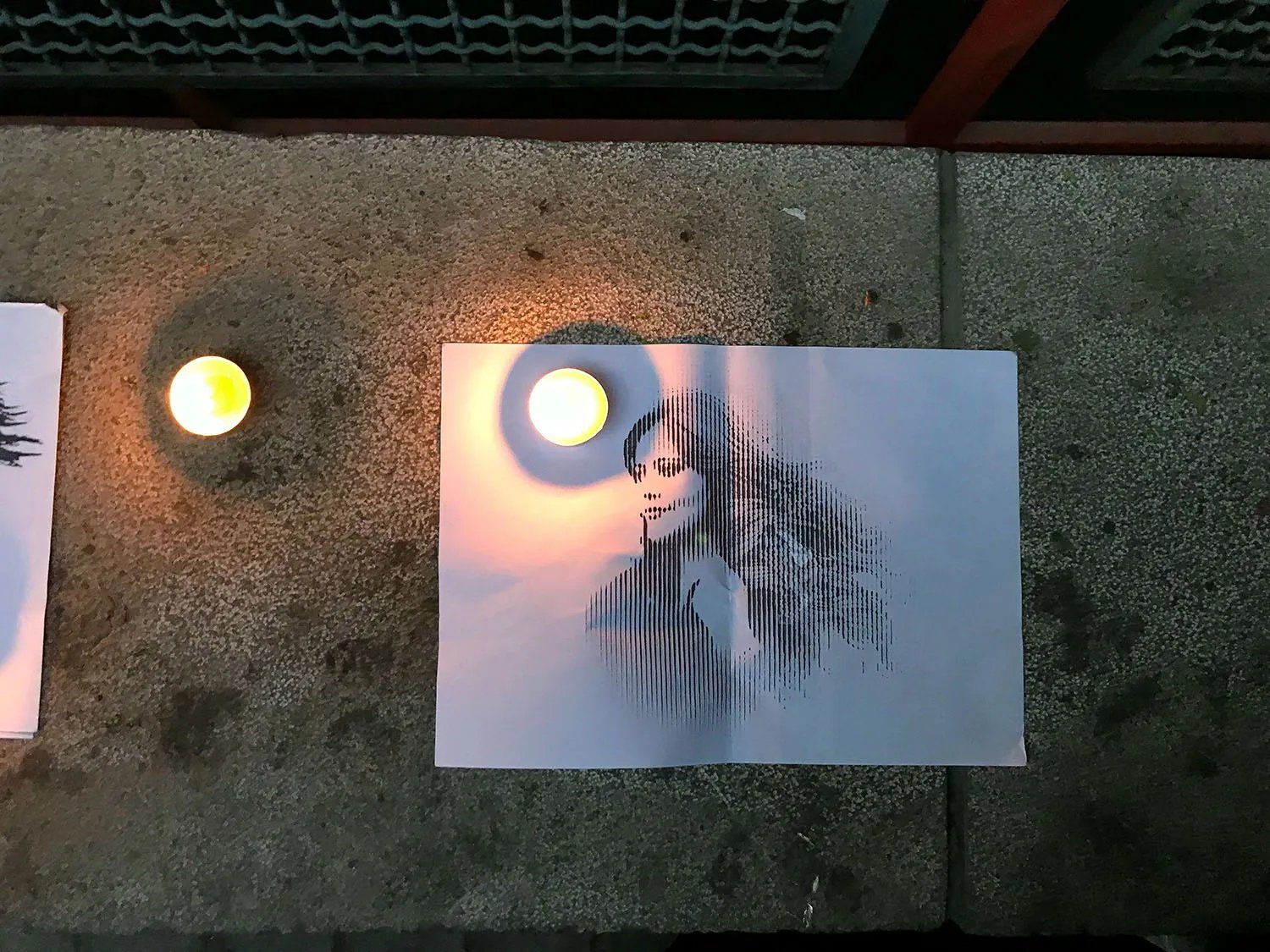

A printed picture of Mahsa Amini rests on the ground in Tehran on Sept. 19, 2022, amid nationwide protests over her death.Middle East Images/AFP via Getty Images

By the time Amini died in 2022, Iranian society had developed its own moral repertoire: Improvised shrines, candlelight vigils, and forms of mourning such as hair-cutting that coalesced in the Woman, Life, Freedom protest movement that followed. That movement has since quieted, but its rituals, slogans, and moral vocabulary permeate everyday social life. Unveiled women remain visible in major cities such as Tehran, Shiraz, and Rasht, despite intensified policing, digital surveillance, and renewed so-called hijab laws.

The families of those killed during the 2022 Woman, Life, Freedom movement continue to hold public memorials that often turn into small-scale protests. Security forces often attempt to block access to cemeteries or arrest relatives, yet these gatherings—traditional ceremonies on the 40th day after death, birthday vigils, poetry readings—remain focal points of moral mobilization. University students still deploy symbolic acts that echo the language of 2022, including silent assemblies, refusal to segregate, and circulating protest poetry. On Persian-language social media, videos of local defiance spread rapidly, sustaining a transnational community of meaning.

The consequence is that the protest movement has shifted from the streets to a diffuse, persistent, and morally charged form of everyday resistance. The state has regained physical control but not symbolic authority.

People gather at Azadi Square during a rally in Tehran on June 15, 2009. Olivier Laban-MatteiI/AFP via Getty Images

A striking development since 2022 is the emergence of politically charged street music performances in major cities. Videos from Iran show large circles of young people gathering around musicians who play songs that have become coded expressions of the protest movement: Shervin Hajipour’s “Baraye,” reworked versions of Dariush and Googoosh classics, Farhad’s pre-revolution protest ballads, Kurdish laments from the 2022 funerals, and pieces by imprisoned rapper Toomaj Salehi. Crowds often sing along and raise lit phones, turning these sessions into improvised memorials.

The presence of female voices is particularly notable—something nearly absent from public space before 2022 due to restrictions on women singing solo. In many of the videos, women briefly sing from within the audience or alternate verses with male performers, prompting applause. Authorities occasionally disperse these gatherings, yet they reappear—suggesting they have become a durable practice.

Two veiled women carry an Iranian flag and a flag of Lebanon’s Hezbollah as they walk past two young people, one of whom is not wearing a mandatory headscarf, before an anti-Israeli protest in Tehran on Sept. 27, 2024. Morteza Nikoubazl/NurPhoto via Getty Images

What has emerged in Iran is not merely anti-regime sentiment but an alternative moral framework with its own coherent principles. First, dignity (keramat), which protesters describe as the core of ethical life, has inverted the regime’s valorization of sacrifice. Second, bodily autonomy (khodmokhtari-ye badan) has become a foundational principle. The body is no longer the vessel of ideological discipline but the site of moral self-ownership. The cutting of hair, the removal of hijab, and the protection of one’s physical integrity serve as ritualized acts of meaning. Finally, truth-telling (rastgooyi) has assumed an almost sacred status. Families of the dead insist on recounting the precise circumstances of killings, resisting state pressure to adopt official narratives. This echoes a long Iranian literary tradition of ethical speech and now functions as a civic ritual.

Taken together, these elements amount to a new moralism—a bottom-up ethic that privileges solidarity over sacrifice, obedience, and ideological purity. Not yet a fully articulated political program, it is nonetheless a coherent moral order.

The centrality of women in this order reverses the Islamic republic’s symbolic hierarchy. The key protagonists of Iran’s contemporary moral imagination are female: Agha-Soltan in 2009, the mothers of those killed in 2019, the schoolgirls who removed their hijabs in 2022, and many women who continue to appear unveiled in public despite cameras, threats, and arrests.

Compulsory hijab is not merely a dress code but the visible cornerstone of the state’s sacred order and a public marker of obedience to divine authority. When women remove their hijabs, they articulate a counter-theology: that dignity, not obedience, is sacred; and that the body is inviolable, not an instrument of political control. The chant “woman, life, freedom” crystallizes this reorientation and asserts a new moral hierarchy.

Even the state’s own rituals reflect its decline. Official parades draw thin, coerced crowds. Once-resonant war commemorations appear formulaic. The vast religious processions of Ashura increasingly separate devotional practice from state messaging. The emotional universe that once sustained the Islamic republic has partially detached from the institutions that claim to represent it.

In hybrid political systems, symbolic authority functions as a substitute for electoral legitimacy, allowing rulers to justify coercion, mobilize supporters, and command sacrifice in moments of crisis. Such a reservoir of symbolic authority enabled the Iranian state to withstand military catastrophe and economic collapse in the 1980s. But its erosion since 2009 means the regime can now mobilize society only through coercion or patronage. This marks a profound shift in the ethos of the Islamic republic.

When citizens elevate their own martyrs, reinterpret religious rituals, and create new forms of collective mourning, they undermine the state’s claim to moral supremacy. A regime can survive economic crisis and international isolation; it struggles to survive a loss of symbolic credibility.

Iran’s experience is not isolated. Societies around the world have turned to symbolic politics and moral rhetoric to challenge authoritarian systems. From Hong Kong’s so-called Lennon Walls, where anonymous protest messages filled public spaces during the 2019 protests, to the spontaneous memorials that appeared across Belarus after the regime’s violent crackdown in 2020, leaderless movements have relied on rituals, mourning, and shared narratives rather than traditional political organization. Iran offers the longest and most sustained example of this trend in the Middle East.

What distinguishes Iran is the depth of its symbolic rupture. The Islamic republic’s narrative—revolutionary Islam fused with martyrdom and anti-imperialism—was once among the most powerful ideological frameworks in the region. Its decline demonstrates that even the most entrenched symbolic orders can be contested from below.

The implications reach beyond Iran. Religious identity and historical memory remain central tools in the political arsenal of Middle Eastern states. Yet Iran shows that once symbols escape state control, they can be redirected. Shia imagery no longer reliably supports Iran’s rulers; it can now indict them. Kurdish mourning rituals attract national resonance. Persian epic poetry has become a language of ethical protest.

The Iranian diaspora adds another dimension. Woman, Life, Freedom demonstrations appeared in cities around the world, from Toronto to Sydney, reflecting a global community of Persian speakers. The massive Berlin rally in October 2022 brought together tens of thousands of Iranians and their supporters in one of the largest diaspora demonstrations since 1979. The movement’s moral vocabulary of dignity and shared grief traveled more effectively than any political platform could.

Foreign governments have been slow to grasp the symbolic transformation in Iran. Policy debates about the country often revolve around its nuclear program, sanctions, and regional proxies. But Iran’s internal evolution matters just as much: A society that has mentally and morally moved beyond its ruling ideology behaves differently at home and abroad. Other countries need to understand not only Iran’s capabilities but also its shifting moral landscape.

None of this means the Islamic republic is on the verge of collapse. It remains a semi-authoritarian system with a strong security apparatus, backed by patronage networks and a political elite still able to suppress dissent. But the state’s loss of symbolic authority represents a deeper kind of weakening that cannot be reversed through repression alone.

Young Iranians have come of age watching protests, funerals, and rooftop chants. These experiences have created a shared archive of memory and meaning that shapes how they interpret legitimacy. A political system can endure material crises, but enduring a crisis of meaning is harder. The state now governs a society whose moral center lies outside the government’s ideological frame.

This tension will shape Iran’s evolution over the coming decade. Even if the regime remains, it will increasingly rule a population that no longer recognizes its sacred vocabulary, accepts its claims to righteousness, or agrees on the moral purpose of public life. That discrepancy will influence prospects for negotiation with foreign powers.

Foreign negotiators often assume that economic incentives will shift Tehran’s calculus. But when a ruling elite feels symbolically vulnerable, it is more likely to take maximalist positions to project ideological consistency. Leaders may appear rigid because international compromise—especially with Western powers—risks deepening their crisis of legitimacy. Conversely, the same moral gap means that Iranian society increasingly interprets foreign agreements not as national achievements but as regime survival strategies. This complicates the political sustainability of any deal.

A woman stands in front of the Blue Mosque in Tabriz, Iran, on Oct. 16, 2024. Morteza Nikoubazl/NurPhoto via Getty Images

The decline of symbolic authority is already visible in elite politics. The regime’s attempts to manufacture public enthusiasm for possible successors, whether clerics or hard-line technocrats, have had little traction. State media campaigns invoking the familiar vocabulary of sacrifice, revolutionary steadfastness, and war valor fall flat among younger Iranians. As a result, rival factions are framing their appeals around material competence—fighting corruption and economic mismanagement and providing sanctions relief—rather than sacred or ideological legitimacy. Even the security establishment has noticeably shifted its rhetoric toward order, stability, and national dignity—terms increasingly emphasized in official statements and state media—and sidelined the language of revolutionary martyrdom.

A further sign of this erosion is the state’s growing reliance on pre-Islamic imagery. This is not a spontaneous rediscovery of national heritage; it is a strategic pivot. For four decades, the Islamic republic kept such symbolism at arm’s length, wary that it competed with the regime’s narrative. Yet especially since 2022, municipalities have unveiled a series of large public artworks drawing on ancient Iranian iconography, often timed to moments of regional tension or war.

The state’s appropriation of ancient heroes reached its peak this year, in light of its need to fight Israel and the United States—and the knowledge that images of figures such as the late IRGC commander Qassem Soleimani would not garner much support.

This sudden embrace of traditional Achaemenid and Sassanian motifs, long cherished by the public but historically sidelined by the state, functions as a tacit admission of ideological exhaustion. It signals that the regime recognizes the diminishing resonance of its revolutionary symbolism and now seeks legitimacy by borrowing from a shared cultural reservoir. In effect, the turn to pre-Islamic heritage is a symbolic concession: an acknowledgment that the Islamic republic no longer possesses a sacred vocabulary capable of unifying the nation on its own terms.

Don’t miss more hot News like this! Click here to discover the latest in Politics news!

2025-12-15 09:48:00