Italy and Spain shake off ‘periphery’ tag as borrowing premiums hit 16-year low

Stay informed with free updates

Simply sign up Sovereign bonds myFT Digest – delivered straight to your inbox.

government borrowing costs paid by Italy and Spain fell to their lowest level compared to Germany in 16 years, as investors reward Rome and Madrid for austerity and grow concerned about rising debts elsewhere in the euro zone.

The additional yield on Italian 10-year debt compared to German bonds – a closely watched measure of the risks associated with lending to Italy – shrank to around 0.7 percentage points this month, the lowest level since late 2009.

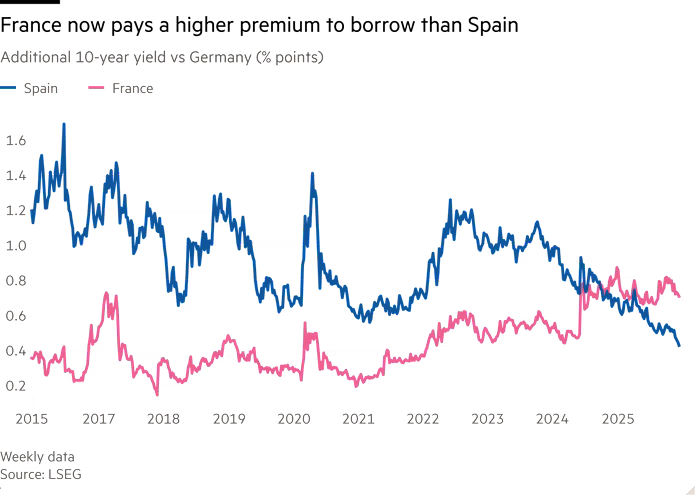

Spain’s strong economic growth helped reduce its ten-year gap with Germany to less than 0.5 percentage points. This is also the lowest since before the eurozone crisis, when high debt burdens pushed up borrowing costs in both countries and raised concerns about the breakup of the currency bloc.

“We are seeing a melting pot in the periphery with countries that were previously considered safer investments, such as France, Belgium and Austria,” said Alice Cotney, head of international interest rates at Vanguard Asset Management. “Markets have long memories, but they are also, with the right stimulus, ready to turn the page.”

Fund managers have warmed to Italian and Spanish debt amid a broad recovery in economic fortunes in southern Europe, arguing that it no longer makes sense to classify these borrowers as “peripheral” in the riskier euro zone.

At the same time, huge budget deficits and political turmoil in France – traditionally seen as one of the bloc’s safest economies – have pushed its borrowing costs higher than those of Spain. Even Germany, the euro zone’s de facto safe haven, has been re-evaluated by markets after launching a trillion-euro spending campaign.

Vanguard’s Cotney expects spreads to narrow further next year, raising spreads in Italy to 0.5 to 0.6 percentage points compared to Germany and Spain to 0.3 to 0.4 percentage points.

Investors point to Spain’s improving economic trajectory and Italy’s prudent fiscal policies under a politically stable government, as part of a broad decline in financial risks for these countries as well as for other former debt hotspots such as Greece.

Ken Egan, director of European sovereign credit at ratings agency KBRA, said the better economic fortunes of southern European countries meant there was a “tale of two Europes, a north-south story”.

He compared the “decisive swing” of southern European economies away from chronic deficits with sovereigns such as France where “obsolete costs, weak growth and heavier spending”. [have] Credit agencies, including Standard & Poor’s, expect French debt to GDP to reach 120 percent in the next few years.

Spain is set to become the world’s fastest-growing advanced economy for the second year in a row in 2025. Thanks to a combination of migration, tourism, lower energy costs and EU funds, the International Monetary Fund expects GDP to expand by 2.9 percent for the country this year.

In conjunction with higher taxes, this growth is set to reduce Spain’s deficit from 3.2 percent of GDP in 2024 to 2.5 percent this year, according to Bank of Spain forecasts.

The Italian economy is much slower, with growth expected to remain less than 1% of GDP until at least 2027. However, investors showed sympathy with Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni, whose right-wing government has shown a strong commitment to deficit reduction, despite pressure from workers grappling with cost-of-living pressures.

Economists say Rome is finally reaping the benefits of previous efforts to curb tax evasion, boosting revenue collection.

Italy believes its fiscal deficit, which reached 7.2 percent in 2023, will reach 3 percent for 2025, allowing Rome to exit the European Union’s excessive deficit measures faster than expected, at a time when Paris is exceeding the borrowing targets agreed in Brussels.

In absolute terms, Italian and Spanish borrowing costs remain high compared to the era of very low or negative interest rates on either side of the Covid pandemic. Overall, Italy’s borrowing costs have risen widely sideways this year at about 3.5 percent, and Spain’s borrowing costs have risen to nearly 3.3 percent.

Trading close to peers that have long been seen as safer bets for investors means these bonds are “entering a completely different regime,” said James McLeavy, head of global and absolute total return at BNP Paribas Asset Management.

“[This is] Beginning to unlock potential global demand for those markets [a broader group of] McLeavy added that very cautious managers of central bank reserve assets may start looking at the debt of Italy or Spain when investing their foreign reserves.

2025-12-27 05:00:00