Lessons From Israel’s 1981 Bombing of Iraq’s Osirak Nuclear Reactor

Since the end of the Israeli bombing campaign and the United States against the Iranian nuclear program in June, the debate has sparked whether it should be measured the time required to measure the program in months or years. However, the most important question is how the bombing can reshape the dynamics of local power in Iran and the national security approach.

Instead of erasing Iran’s nuclear ambitions, the process may have motivated the system to cut all forms of international cooperation and intensify its program. Through Iran’s leadership to go on its own, the strikes created the serious uncertainty surrounding its following movements – a scenario reminding us of a remarkable way to look at the effects of the Israeli strike on the Osirak reactor in Iraq in 1981.

Since the end of the Israeli bombing campaign and the United States against the Iranian nuclear program in June, the debate has sparked whether it should be measured the time required to measure the program in months or years. However, the most important question is how the bombing can reshape the dynamics of local power in Iran and the national security approach.

Instead of erasing Iran’s nuclear ambitions, the process may have motivated the system to cut all forms of international cooperation and intensify its program. Through Iran’s leadership to go on its own, the strikes created the serious uncertainty surrounding its following movements – a scenario reminding us of a remarkable way to look at the effects of the Israeli strike on the Osirak reactor in Iraq in 1981.

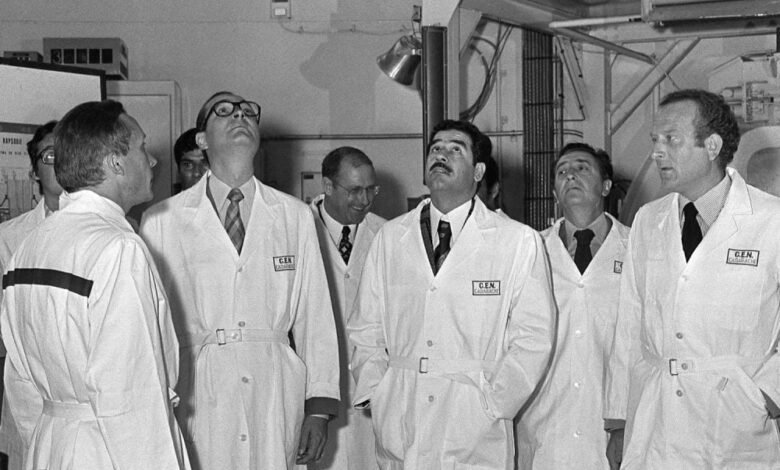

In the late 1970s, during a period of oil revenues and strong economic growth, Iraq decided to launch its nuclear program. In 1976, the government bought the civil nuclear research reactor – “Osirak” – from France as the first element in this program.

Osirac reactor – which was dismantled with the fact that France has provided Iraq with enriched uranium to 93 percent of purity – caused fears that Iraq intends to convert the resulting plutonium in the facility towards building a nuclear weapon. However, the design of the reactor made it technically difficult to do so, and the same reactor was very small and closely observed to form the basis of the weapons program. The Iraq program instead was largely exploring, and its scientists had no explicit political authorization to develop a weapon.

In a sudden air strike on June 7, 1981, Israeli aircraft destroyed the OSirak reactor before being fed. Israel described the mission as a resounding success, and soon became dedicated to the traditions of politics as a model to eliminate an emerging nuclear threat. During the period before the invasion of the American Iraq 2003, senior Bush administration officials publicly attributed to the Ozirak attack with Iraq to prevent nuclear weapons before the 1991 Gulf War.

This successful novel has blocked the true consequences of the strike: aimed at strangling the nuclear aspirations of Iraq, and instead, the bombing was largely shook. The vulgar system, obsessed with its own security, concluded that it must develop a nuclear deterrent – and that he should do this secretly if he hopes to succeed. The shelling also assembled officials and engineers from the lowest level of success in what is now considered an urgent issue for the national defense.

Within months of Israeli bombing, the Iraqi president and the dictator undisputed Saddam Hussein agreed to launch a secret nuclear weapons program, with great funding despite the ongoing war with Iran. The effort was backward and inconsistent with political, suddenly became a national priority. From 1983 to 1991, employees rose from 400 to 7,000 worlds, while the annual budget for the program increased from $ 400 million to 10 billion dollars.

About the newly enabled nuclear scientists in Iraq focus on producing plutonium to enriching uranium. Although uranium enrichment is more technical, costly and time to take a long time, it does not depend on foreign fuel supply, and therefore it was easier to hide it. To secure the necessary technology, industrial and intelligence agencies in Iraq built a secret purchasing network that used front companies and embassy employees to acquire equipment from German, Austrian and Japanese suppliers.

By the late 1980s, the program was approaching maturity. Iraqi officials expected the start of the cold tests of the nuclear system by 1993 and aims to produce enough uranium very fertilized for one bomb annually starting in 1994.

In the end, Saddam’s recklessness, not an Israeli air strike, which prevented him from obtaining the bomb. After Iraq’s invasion of Kuwait in 1990, a desperate collision program was launched to build a weapon within six months – an effort that the nuclear establishment has known from the beginning. After the 1991 Gulf War, Iraq was forced to allow weapons inspectors to enter the country as part of the armistice agreement. Soon after their arrival, the inspectors found a program on the threshold of nuclear weapons capacity.

It is very similar to the effects of Israel Israel, the bombing campaign against the Iranian program risks a regional opponent to go to the ground and intensify its efforts. For solid times in Iran, the lesson may be clear: only nuclear deterrence can prevent future attacks. The strikes may change how Iran is going, but it is possible that the regime’s intention to cross the threshold.

It is clear that Iran today is not the same Iraq in 1981, but it is difficult to ignore similarities. Just as the Ozreen strike was born in a political consensus in Iraq and agreed on the regime with ambitious nuclear entrepreneurs, recent statements by Iranian leaders indicate that the attacks have encouraged the appearances.

Many analysts note that the war has accelerated the transformation of power in Tehran from clerics into generals. These new leaders may be more rational, but also more aggressive, suspicious of diplomacy, and they are likely to give priority to staying through deterrence instead of sharing. The strikes may also cause a renewed sense of urgency between nuclear scientists and Iranian weapons engineers, just as many Iraqi engineers have embraced Saddam’s nuclear strategy after the destruction of Osirac.

The system is likely to be less prepared to follow another nuclear deal, and it has a great incentive in the attempt. For authoritarian regimes throughout the region, nuclear diplomacy has often ended. After the Libyan powerful man, Mamar Gaddafi, dismantled his weapons program for comprehensive destruction, he was later targeted in the NATO bombing campaign. In Iraq, Saddam was no longer an active nuclear effort before the United States invaded in 2003, when he was removed, tried and hanged.

These precedents loom on the horizon in Tehran. Even moderate figures will now feel misleading: schedule another round of talks with the United States on June 15 The Iranians intentionally calmed down a false sense of safety before the strikes began. This will make it difficult to resume negotiations and encourage militants who have long argued that the West was not acting in good faith.

Also, the air strikes have been circulated again in known problems of unknown problems. Like how the unreasonable secret secret program of Iraq has flourished after Ozerk, Iran’s withdrawal from the IAEA international supervision (IAEA) this week will hinder severe efforts to determine the location of future confidentiality facilities. The ancient Iranian nuclear deal has been abandoned due to fears that Iran may have been building secret facilities, but concerns about secret facilities only exacerbate after military strikes. The end of Iranian cooperation with the International Atomic Energy Agency is a set of upcoming things.

When considering the differences between Iraq and then Iran now, the strike decision appears more dangerous. Today, Iran’s population is six times and its economy is 10 times from Iraq at the time. It is also more technologically developed, much better organized, and is better able to protect its nuclear program. Regardless of the amount of damage to Iranian facilities, and despite the assassination of many nuclear scientists, Iran maintains all the technical experience that needs to resume its nuclear program if it chooses.

Iran suffers from a number of weaknesses that may restrict its ability to rebuild its facilities. Israel’s campaign revealed the extent of state institutions penetrated through foreign intelligence, which Iran is seeking to address through a wave -like wave of detention and executions. Iran is also much more isolated than it was a few years ago, with traditional allies such as Russia and even agents like Hezbollah provides more rhetorical support.

But in the long run, even these faults may enhance the logic of nuclear deterrence, which persuaded Iran’s leaders that it was only an atomic weapon that can secure the regime against attempts to overthrow it. Moreover, Iranian leadership will not have missed that the North Korean regime is still alive.

Military strikes may feel decisive in their direct heels, but their second and third -class effects are often revealed in a slow movement. Iran’s response may not come immediately, but it may appear in calm decisions to stay away from diplomacy, reshape facilities in the shadows, and build what he may now see as an essential way to survive.

Those outside Iran who want to avoid this result will need to abandon the attractiveness of rapid reforms in favor of a long -term strategy that restores in the evaluation of the Iranian leadership and the goals it leads now.

Don’t miss more hot News like this! Click here to discover the latest in Politics news!

2025-07-07 10:45:00