Trump’s Critical Mineral Drive Worries Alaska Natives

Elim, Alaska – About 120 miles south of the Arctic Circle, this Inupiaq village lies between the mountains and the turquoise waters of Norton Bay. Children scream and jump in the streets, and residents race across the open roads on ATVs. Elim is known as a checkpoint during the Iditarod, not a destination for tourists and cruise ships.

Recently, however, the village has become noteworthy because of something beneath the surface: Just 30 miles up the Topotolik River, Alaska’s largest known uranium deposit lies on a 22,400-acre property called the Boulder Creek Site. For the people of Elim, this geological wealth is not a promise but a threat to their way of life. The depot is located near the headwaters of the Tubutolik River, where locals fish, forage berries, and hunt moose, as they have for centuries.

Uranium, highly prized for its use in commercial nuclear reactors, Navy submarines and other defense applications, is one of several Alaska resources attracting public and private sector interest. It has gained increasing importance in recent years with the rise in demand for low-carbon nuclear energy. Although the United States was once a major uranium producer, today it supplies only a small share of its own needs and relies heavily on imports. Since Russia’s large-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022, which highlighted vulnerabilities in the global nuclear fuel supply chain, the Biden and Trump administrations have moved to bolster domestic uranium mining and enrichment capacity. Only last November was uranium returned to the US government’s official list of critical minerals.

But beyond Washington, these national priorities are raising alarms in communities closest to where new mining activity could occur. Elim residents warn that even exploratory drilling could contaminate the wildlife that supports the village. Emily Murray, vice-chair of Norton Bay Watershed Council, said: “If they take away our livelihood, we will starve.”

Amid President Donald Trump’s aggressive campaign to shore up supplies of critical minerals in the United States — backed by new executive orders, rollbacks of environmental protections, and a fast-track federal licensing system — Elim has become a test of how far Washington is willing to go, and how much indigenous communities stand to lose.

-

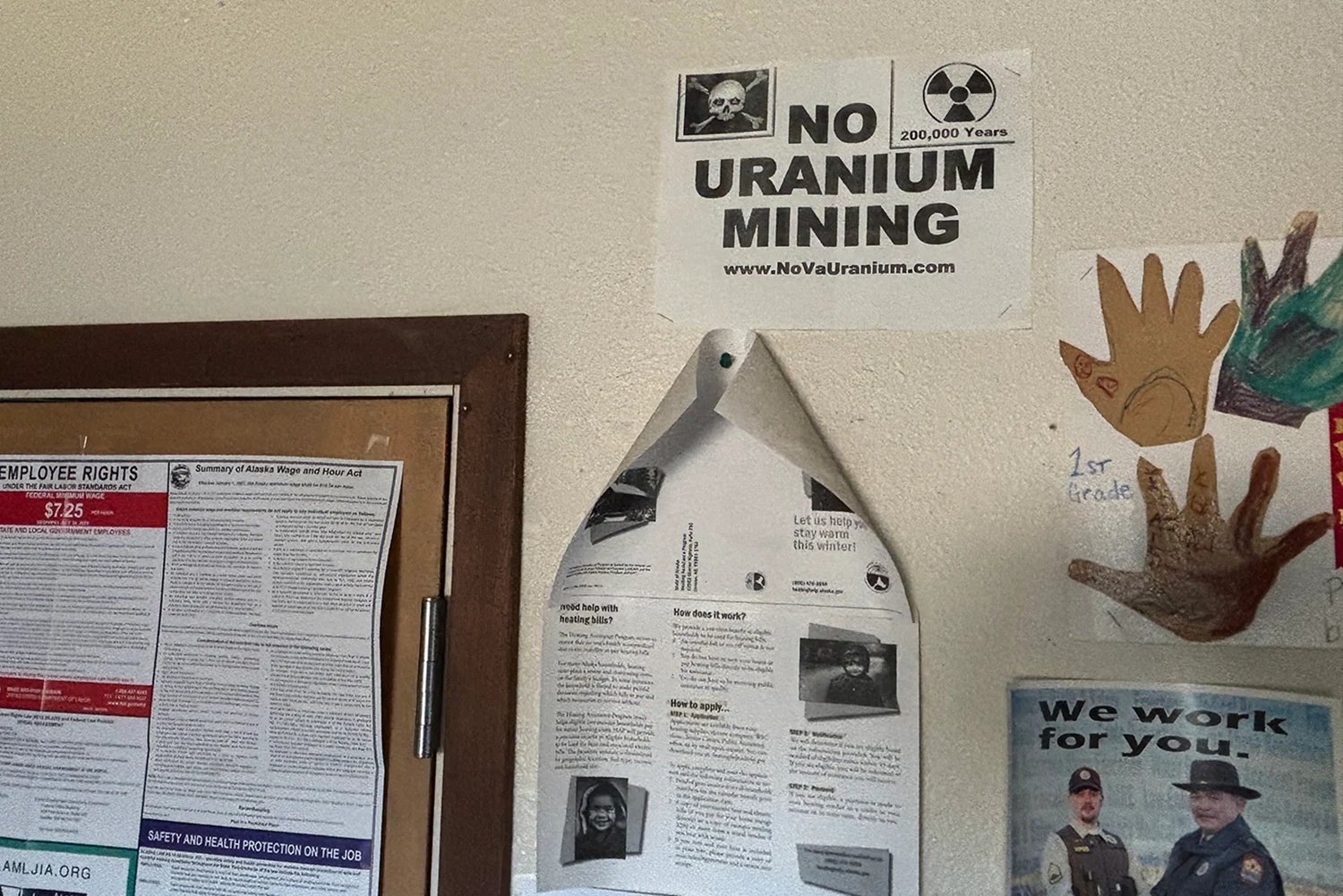

Artworks and banners created by school children in Elim in protest against a proposed uranium mine nearby.

-

A “No uranium mining” sign hangs at the entrance to the administrative building of the city of Elim in September 2025.

Murray has been fighting this battle against creep mining operations for the better part of two decades. It started in the summer of 2005, when Canadian mining company Triex Minerals began prospecting for uranium in Boulder Creek.

Alarmed by the potential dangers, villagers organized protests, letters and campaigns targeting state officials. This effort included a group Murray helped launch, Elim Students Against Uranium, which was supported by the local tribal council. Trix pulled out in 2008, but since 2024, Elim residents have rallied again — this time against Panther Minerals, whose exploration in the same area has revived old concerns about the safety of the watershed.

Residents again organized, wrote letters, and testified at hearings. Last March, for example, Kylie A. wrote: Moses, an Elim High School student, wrote in a letter to Gov. Mike Dunleavy that the leach solutions and water needed to extract uranium could contaminate groundwater, urging him to “be aware of the long-term future negative impacts on our land, environment, animals and humans.” Did not receive any response.

So, when Panther Minerals suddenly pulled out of the property last July, the relief in the community was palpable, but short-lived. For Elim, Panther’s exit is a reprieve that may disappear with the next investor. Mining claims on the property remain active. David Hedderly Smith, the geologist and prospector who made these allegations, did not respond to this Foreign policyRequests for comment.

“It may be the largest uranium deposit, or, you know, group of deposits on American soil,” Hedderly Smith told local media during the recent exploration. Elim could become the “Uranium Capital of America.”

At present, it is impossible to know the true size of the uranium deposit. But given the United States’ current obsession with critical minerals, there is no sense that the pressure on Alaska’s mineral-rich lands will ease anytime soon. Residents say this is what makes the moment seem so perilous.

For activists like Yasmin Gmiwuk, who opposed (with the Tribal Council) Panther drilling, the state’s handling of the process of permitting uranium drilling has deepened community distrust. Despite extensive public comment, joint resolutions from tribal and local governments, and formal requests for government-to-government consultation, state regulators proceeded to grant Panther the permit anyway, Jimiuk said.

“We were able to collect over 100 comments about the communities’ concerns, and still are [Alaska] “The Department of Natural Resources went ahead with the permit,” Jimiwuk said. “After that, I felt desperate, like they were going to go ahead with it anyway, even with the entire district opposing it.”

It is this feeling – of being heard but not being heard – that now fuels Elim’s determination to defend her turning point when the next company, or the next administration, comes knocking.

One of the first dwellings in Elim, now abandoned, was built by the ancestors of those who live in the city today.

Among the important minerals found in Alaska, China is also a major global exporter of antimony and zinc, making the development of domestic alternatives in order to take China out of the supply chain increasingly attractive.

For decades, Alaska has been a major supplier of resources for national defense and energy needs. Although the previous two Democratic administrations paid significant attention to Alaska conservation and wildlife protection, Trump reversed many of those policies in his second term and accelerated efforts to extract Alaska’s resources.

Shortly after taking office last January, Trump issued an executive order aimed at exploiting Alaska’s mineral wealth by speeding up the approval process for mining projects, including those on Native American lands. Protections covering 13.3 million acres in the central Yukon were canceled in December, and FAST-41, a program designed to streamline the permitting process for projects deemed critical to national defense, has increased risks for communities near extractive operations.

Projects that had previously been blocked or delayed, such as the controversial Ambler Access Project, which would create a road through the pristine Brooks Mountain range in northern Alaska to access copper, zinc and cobalt deposits, have been revived despite significant local opposition.

However, many of the Trump administration’s ambitions conflict with the harsh reality of resource extraction in the Far North. The region’s harsh winters and high costs of transportation, labor and construction often outweigh potential revenues, with mines often not reaching profitability before 20 years of operation.

Troy J. said: “It’s often said that Alaska is key to securing U.S. energy security, and I’m not sure these numbers support that at all,” said Bovard, director of the Center for Arctic Security Resilience at the University of Alaska Fairbanks. “All the excitement behind critical minerals… we’re not ready to do that at all.”

Ironically, Alaska is uniquely suited to natural resource development, but not in the ways the Trump administration seeks. Offshore wind, hydroelectric power, and geothermal energy—resources that the administration has refrained from providing elsewhere—are all plentiful, cost-effective, and reliable in the Far North.

said federal officials working on Arctic cases, who requested anonymity because of potential retaliation Foreign policy That there has been tangible progress toward domestic investments in renewable energy and climate adaptation measures during Trump’s second term. Many of these officials said Trump’s approach to Alaska was seen as reckless and irrational when it comes to fossil fuels and precious metals, closer to piracy than pragmatism.

Local residents worry that Trump’s approach to resource extraction will not help preserve the land and the people who depend on it. The money brought into Alaska through these commercial arrangements rarely has a lasting impact on public services, but rather benefits out-of-state refiners and defense contractors.

“This supposed idea that we can solve our problems by extracting more: You can look at our history, and we haven’t done that,” said John Gedecke, who owns a lodge in the Brooks Range. “Our population is declining. The money we spend on education is declining. And yet we have had one of the biggest oil booms in the country’s history. We cannot climb out of poverty here.”

Critics say history makes the current moment particularly troubling. Hal Shepherd, an attorney hired to support Elim’s mining resumption effort, fears a bleak future for the village and similar communities as the Trump administration seeks to extract more from Alaska. “I’m afraid that if there was a bigger and bigger company that would have more resources [comes in]“They’re going to be in trouble,” he said. “It’s going down the track very quickly.”

A view from a small regional plane shows the landscape of the Seward Peninsula in September 2025.

For generations, Alaska Natives have been pushed to the margins of decisions about land and resources — from World War II military installations that left behind leaking fuel barrels to more recent oil and mining projects that were approved without meaningful consultation. Today’s national push for critical minerals is only the latest chapter.

With the Arctic becoming a strategic frontier in a warming world, melting sea ice opening new shipping lanes and its minerals the focus of competing global powers, Washington’s focus on security and supply chains has overshadowed the needs of the people who live in the region. These ambitions often benefit military and corporate interests, while the risks fall on indigenous communities whose cultures depend on the health of their lands.

At Elim, those risks are not abstract. As residents learned of the devastating effects of former uranium mining on Navajo lands in New Mexico, the threat of a similar fate became more real. Beverly Nakarak, a local resident, remembers learning as a teenager that “an entire village got sick, got cancer.” (Since the peak of uranium mining on the Navajo Nation during the Cold War, the community has faced much higher rates of cancer, kidney failure, and other lung diseases.) [the mining company] “I didn’t care that people would get cancer and die,” Nakarak said.

For families like Nakarak’s who depend on the Tubutolik watershed for their livelihood, the risks are personal. Nakarak, who works as a health aide, says that people in her community previously tended to live to very old ages, often beyond 100 years. Now, with their diet and environment increasingly disrupted, she says they started falling ill decades earlier.

Given this, many in Elim fear that another wave of industrial pollution could jeopardize the health and well-being of future generations. “If you’re not going to pollute our land, do it,” said Wayne Moses, a tribal representative. “But I just got another grandchild, and this baby needs to enjoy what we have now.”

This project was supported by a grant from the Ira A. Lippman Center for Journalism, Civil and Human Rights at Columbia University in association with Arnold Ventures.

Don’t miss more hot News like this! Click here to discover the latest in Politics news!

2026-01-16 19:00:00