Will Trump Order an Attack on Venezuela?

The United States hasn’t yet declared war on Venezuela—but it’s getting closer. This week, U.S. President Donald Trump issued a blockade on sanctioned ships in and out of Venezuela ports, a decision that led authoritarian leader Nicolás Maduro to order his navy to escort other ships in the Caribbean. With a massive U.S. Navy presence nearby, it’s not difficult to imagine an unintended escalation.

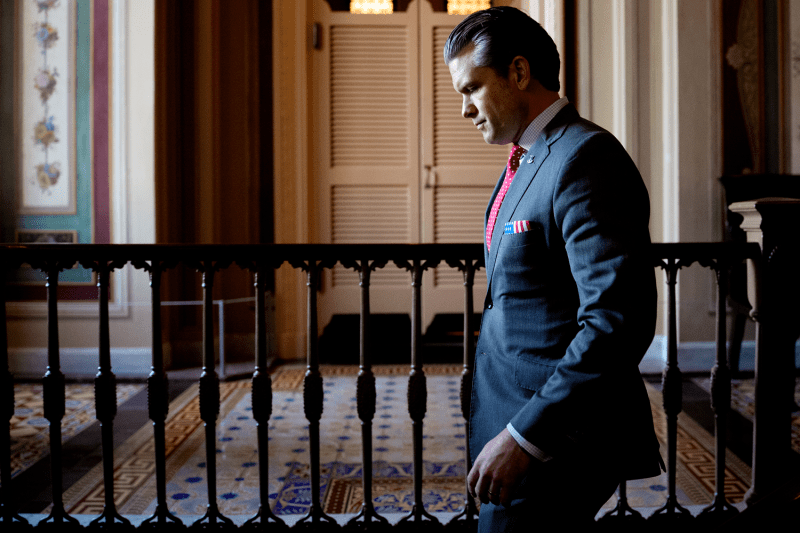

What does the White House actually want in Venezuela? What could a war look like? And were Maduro to magically agree to leave the scene, what happens next? On the latest episode of FP Live, I spoke with James Story, a former U.S. ambassador to Venezuela under both the Trump and Biden administrations. Subscribers can watch the full discussion on the video box atop this page or follow the FP Live podcast. What follows here is a lightly edited transcript.

Ravi Agrawal: What’s the likelihood that we will see actual U.S. military action on Venezuela?

James Story: I think it’s about 80-20.

RA: This week’s blockade strikes me as making things a lot more tense. The fact that Maduro has ordered his navy to accompany ships carrying petroleum products out of Venezuelan ports means there’s a much higher chance of some sort of confrontation on the high seas, right?

JS: It increases the odds of a mistake being made by either side. What’s really important here is to unpack which ships Maduro is escorting. I believe he wouldn’t make the mistake of escorting a sanctioned vessel; a vessel that was stateless, such as the Skipper, which was the vessel that was taken last week; or another vessel that is part of the ghost fleet. Here Maduro is going to have to be very careful, but it’s going to have a massive impact on the regime’s ability to export oil regardless.

RA: What percentage of ships going in and out of Venezuela are actually sanctioned?

JS: The most recent numbers I’ve seen are around 40 percent. I often have advocated for some directed action against stateless vessels or vessels that were spoofing their automatic identification systems (AIS). According to the International Maritime Organization, vessels of a certain tonnage have to display their whereabouts. Some of these ghost fleets have been serving the Russians, with their exports of oil; they’ve served Iranian interests, Chinese interests, and others. They indicate they’re in one ocean when they’re at a completely different place. In the case of the Skipper, they were flying a Guyanese flag, but they’re not registered in Guyana. So taking the Skipper was a righteous, judicial action because it was a stateless vessel.

RA: I’m curious how long Venezuela can last in a blockade scenario. Even though this blockade is currently just for sanctioned vessels, that could easily escalate. Given that all of this is to put pressure on Maduro, how long does he have in this scenario?

JS: One thing that’s not particularly sexy to unpack is how much storage capacity Maduro has for the oil. You have to remember that what Venezuela produces is a very thick, tar-like oil that requires significant inputs of naphtha or light sweet crude in order for it to be pumped out and moved to other refineries or sent on ships. I think they have a storage capacity of about 35 million barrels. If they’re producing close to a million barrels a day, they currently have around 27 million barrels of oil in storage. That means if they don’t export, they’re going to run out of storage capacity soon. And when they run out, then what happens? If you stop producing oil in Venezuela, it creates big problems for the fields themselves. That is why, regardless of a license to export oil, Chevron never stopped pumping oil in Venezuela throughout the episode we’re living in. To do so would be to damage its equipment and ruin the field.

RA: Moving back to the idea of potential military action or regime change, what is the White House’s rationale? We’ve heard a lot of different reasons. We’ve heard drugs, oil, maybe critical minerals, maybe democracy promotion. What is the main reason?

JS: This could be an “and, and” scenario, but let’s start with the world as Trump sees it. He ran on a platform that said criminality was rampant in the United States and that the impact of migration was having a deleterious impact on American society and our economy. This is kind of the perfect storm of those two issues, because during the Maduro dictatorship, 25 percent of the people of Venezuela have fled their country. The vast majority of these are good, honest, hardworking people who are merely seeking a better life for themselves. But there have been younger people who have gotten into criminality. There are elements of Tren de Aragua which have been exported across the region. This is a drug-trafficking, foreign terrorist organization. You have criminals directly linked back to some of the diaspora from Venezuela. So this is an issue for him.

RA: We’ll go through all the reasons one by one, but Jimmy, just staying on criminality and drugs, one immediate refutation of that argument is that criminals come from a lot of places, drugs come from a lot of places—and the United States doesn’t attack them all. And in any case, most of Venezuela’s drugs go to Europe, not to the United States. Add to that, Trump recently pardoned Juan Orlando Hernández, a former Honduran president who was actually convicted of smuggling hundreds of tons of drugs to the United States. So the idea that invading Venezuela just because of criminality and drugs doesn’t hold water as the reason for doing this.

JS: I’m not suggesting that the policy is coherent. I’m just telling you what he’s thinking. There is a lack of coherence here on this issue, but Trump ran on that platform, and he directly connected migrants, Venezuela, and criminality.

Most drugs in the United States are produced in Colombia. No fentanyl comes from either Colombia or Venezuela. And drug-trafficking organizations are not democratic entities. They don’t have committees to make decisions. They will simply move their drugs from fast boats to other modalities. I ran counternarcotics in both Colombia and the Western Hemisphere. And I would submit that we’re going to become blind in the region because our partners will quit giving us intelligence.

RA: The U.K. and the Netherlands have already reportedly begun to hold back some intelligence.

JS: Of course. I also can’t imagine a world in which Colombian President Gustavo Petro would want to provide us with intelligence that would lead to the death of Colombian citizens, when he’s trying to up the chances of his political movement ahead of elections next year. So we’ve got problems here when it comes to sharing intel.

One thing that I like to say is transnational criminal organizations are transnational: They don’t respect borders. So to work on this problem, you have to work transnationally, which is how we’ve always done it. The intel we get from grabbing the crew, the intel we get from the drugs—we can even do DNA analysis to tell where exactly the cocaine came from—these are things that we’re losing. I don’t think that this will age well.

RA: Let’s look at the other supposed rationale for this, which is oil. Venezuela has some 17 percent of the world’s proven oil reserves, but it only produces 1 percent of global crude. As you mentioned earlier, the crude it does produce is low-quality, heavy crude that needs a lot of refining, and it could take many years to pay off. Talk a little bit about how you see oil as a potential rationale for any kind of U.S. involvement in Venezuela.

JS: I think it’s pretty far down the list. I personally put it at the fifth, sixth, or seventh reason for doing this. I put the instability driven by 9 million migrants across the region higher. Even the crimes against humanity accusations in the International Criminal Court is higher on the list of reasons [for ousting Maduro].

So there are lots of other reasons for this. But it is true, however, that the Gulf refineries in the United States were set up to receive sour heavy crude from Venezuela. You get more products from that heavy crude, including diesel, for instance. A lot of those refineries have since been retooled over the years with the recognition that they weren’t getting as much heavy crude. If you look at where we’re getting that heavy crude from now, it’s from the tar sands from Canada, certainly a more reliable partner for producing that part of the energy matrix.

RA: Let’s go through all the other reasons that have been suggested for why we are where we are with Venezuela. The other one is regime change: Maduro is a bad leader, and the United States wants him to go. There could ultimately be some sort of connection to Cuba as well.

JS: I wouldn’t even call him a leader. He was an accidental president when he won elections. Let’s not forget that he lost an election last year. It’s really important for people to remember this fact when President Petro attacks María Corina Machado or decides that Maduro is just a beleaguered leader in the region. According to the law in Venezuela, you have to show the proof of the vote. It’s called actas, the pieces of paper from each voting station. The opposition actually showed about 85 percent of those actas. The dictatorship never did. So there is a question here about democracy. Even under an unfair electoral situation, the people of Venezuela spoke very loudly that Maduro was no longer legitimate. He hasn’t been legitimate for quite some time. That is an issue.

This is also unfinished business from the first Trump administration, to some extent. Venezuela is turning into a failed state, harboring international criminal organizations and foreign terrorist organizations: the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC), the National Liberation Army (ELN), Hezbollah, and others. We have a failed state that is in league with our strategic competitors, that is a haven for criminal groups and is destabilizing the region. Those are all reasons enough to do what we’re doing. This was never a counternarcotics mission. This has always been a regime change mission.

RA: You’ve served as an ambassador during both the first Trump administration and the Biden administration. I’m curious how all of this gets gamed out on the back end. All of the rationales you’re mentioning make sense. But where they stop making sense to me is A) this could be against international law, and B) where do you stop? There are many bad leaders or authoritarians around the world. There are many countries which are the source of instability, drugs, and criminality. Think of North Korea, for example. Think of Iran. Are we going to now try to push for regime change in countries that we think are doing poorly? Remember, Trump came to office saying he’s not a regime change guy, he’s not going to get involved in foreign conflicts the American people don’t want.

JS: There’s been an evolution of some of that thinking, I’d say. You can read the new National Security Strategy a few different ways. There’s an emphasis on our hemisphere. I don’t know if the Trump corollary to the Monroe Doctrine is to speak brashly and make a deal, which is different than “speak softly and carry a big stick.” But he’s certainly interested in what’s happening in our hemisphere. What happens in Venezuela has a direct impact on the United States. We have 800,000 Venezuelan migrants who have made it to the United States, 3 million in Colombia. This affects everything from political stability to economies across the region. So this is qualitatively different from some of the other examples you provided.

On the back end, you’re exactly right, Ravi. You have to think through the second-, third-, fourth-, and fifth-order effects of regime change. I would submit that this is a closer case to Panama than it is to Libya, Afghanistan, Iraq, or Haiti for a few reasons. One, 70 percent of the Venezuelan people voted Maduro out of power. We know that he’s unpopular and we know that the people won’t change. That’s an important thing. Two, this is a country that is ready for a Marshall Plan because they had the best hospitals, the best education, the best everything in Latin America at one point in time. That can all be rebuilt. The next reason is there are no ethnic, sectarian, or religious differences. In fact, you’d be surprised to know how many people in the dictatorship and the opposition are actually first cousins or went to college together. They know each other. There’s a national ethos here.

I’m not suggesting that it’ll be easy, and I’m not suggesting that democratic restoration will be linear. There will be fits and starts. The question I have is: If we do some activity, if that 80 percent chance of some kinetic action happens, to what extent is the administration prepared to ensure the peace and stability of Venezuela while they re-institutionalize the government and provide security, so that its democratic experiment can get back off the ground?

RA: I want to get to that in a moment, but let’s interrogate the Panama 1989 example a little bit more. Critics of the Panama analogy often point out that there were already 13,000 troops permanently stationed in Panama, that U.S. intelligence had incredible detail about [dictator Manuel] Noriega’s command nodes, and there was a history of regular drills in the region, which made Panama’s army desensitized to an actual attack. That’s partly why when George H.W. Bush issued the order to send in 14,000 more troops, it was a sharp, short war and seen largely as a success. Those things are different from what we have in Venezuela.

JS: There are two different things here. One is how do you effect regime change? I agree with you. That will be completely different. The second is what does it look like after the regime has changed, what comes next? That’s where I think the parallels actually stand up a bit better. One of the parallels is negative: There was score settling. It was pretty violent for a few months right after Bush’s Operation Just Cause. But the end result is a democratic, middle-class, secure country that is a net positive to the region.

In the case of Venezuela, whatever action the administration takes, I’ve been counseling very strongly that while it’s relatively straightforward to take out their offensive capability, to destroy their air force and navy, that would take a matter of hours for the U.S. military currently in the Caribbean—

RA: Can you just expand on that a little bit more? Venezuela does have S-300 missile defense systems. This is also a population that is heavily armed with guns, many of them actually U.S.-made.

JS: What I’m suggesting is we could blow up their navy and destroy their air force on the ground very quickly with our standoff capabilities, regardless of their S-300s. All those airplanes, the F-18s, the B-1 bombers, the B-52s, that’s all to figure out where their radar and installations are. So we have a good idea of how we go about doing that. But I don’t think we should do it because there’s no reason to create an additional set of enemies inside the country. I think it’s a bit of a waste and sends the wrong signal. You’re going to need the armed forces of Venezuela to provide a modicum of stability and security because of all those illegal, armed groups we talked about earlier.

I’ll tell you, there’s not one pilot in Venezuela—and I would bet the house on this, y’all—who will get in his Sukhoi and go up against an F-35. They won’t do it. So the question is, then, why destroy them? Or if we were to destroy them, destroy them on the ground when nobody’s in them. That’s a possibility. There are ways for the administration to have kinetic activity that falls short of that. We learned in Iraq, going back to that example, that de-Baathification was a bad idea. We need to figure out who we can trust. The end result, like every other transition in Latin American history, is that you’re going to have to hold your nose and have transitional justice. Some people that you didn’t like before are still going to be around the day after.

RA: Let’s talk about the day after, assuming that Maduro somehow is deposed, even though it would be illegal, even though there would be a lot of criticism from countries in the region, globally, at the U.N., and beyond. Let’s just game this out. What happens the next day?

Would any opposition leader, whether it’s María Corina Machado or another, have legitimacy? Or would they be seen as coming off of the back of an American intervention, and therefore not legitimate?

JS: Edmundo González is the legitimate elected president of Venezuela. They have the proof. He won the election. María Corina Machado won a primary and she is the undisputed leader of the opposition. She’s the moral leader of the country. She just won the Nobel Peace Prize.

So the question then becomes, how do you build that transition? How do you provide for the transition? How do you make certain that the transition holds? Were I Edmundo González, I would make very public my plan for the transition, to let everybody know where they are.

You spoke of the legality of removing Maduro. The objective of the U.S. government is that somebody close to Maduro shows him the exit, or he himself takes it. He makes his own decision to leave. But legally he’s not the president because there’s somebody who has been elected president.

RA: But by that token, there are a lot of “illegal” leaders around the world, right?

JS: Sure. Those that have a direct impact in the United States are fewer, but I think here the real question for me is if I’m a general and I’m going to act against the Pablo Escobar figure that is Nicolás Maduro, I need to know what’s waiting on me on the other side of this process. What does the transitional justice system look like?

I think it’s important and incumbent upon María Corina, as the leader of the opposition, and Edmundo González, as the elected president of the country, to lay out that vision. They say there’s a plan. That’s great. I would make the plan public. Then my question is, to what extent is this administration going to be willing to engage?

RA: Is the military a crucial player in any sort of transition loyal to Maduro? Would they switch allegiance to someone else, if need be?

JS: You can’t swing a dead cat in Caracas without hitting a flag officer. They have several thousand generals and admirals. I think they have more than all of NATO combined. Some of them have been involved in everything from narcotics trafficking through the Cartel de los Soles, to illegal gold exports and even crimes against humanity, murder, and the kidnapping of American citizens. What I’m suggesting is that some of these people may not be able to be rehabilitated. But within the military, you have a large percentage that are ready for change as well.

This military is a shell of what it used to be. They have a desertion rate of about 40 percent among the lower ranks. And it’s key to remember that members of the National Guard in Venezuela were the ones who handed over the actas, the proof that the opposition had won.

There’s no love for Maduro within the military. He didn’t serve there. There are two other actors who did and are keeping the military in check: Vladimir Padrino López, the longtime head of the military, and Diosdado Cabello, a very nefarious actor who’s responsible as well for the internal security services.

I would add one more, because Venezuela is an existential problem for Cuba. Cuba lives off free hydrocarbons from Venezuela. Losing Venezuela would be a very, very harsh blow. They infiltrated the military and tried to coup-proof it after 2002. They provide direct security to Maduro; they provide intelligence and make sure that people are loyal. The question I have for those who are looking at this closely—and I’m out of government now—is has someone been identified to run the military as they re-institutionalize, as they bring it back under constitutional and civilian control?

RA: We’re gaming out some of the potentially rosier outcomes here, but I want to flip the switch on this. What keeps you up at night? When you’ve got 10 or 11 percent of the U.S. Navy stationed outside Venezuela, what could go wrong here? What should we keep in mind about all the scenarios that could end up being disasters?

JS: Any military leader will tell you that plans last until the first bullet flies. Then you’re playing jazz. You’re just improvising from then on out.

What has kept me up at night, even when I ran counternarcotics in Colombia between 2010 and ’13 and for the Western Hemisphere from 2013 to ’15, is that the 5,000 man-portable shoulder fire and anti-aircraft missiles in the country could fall into the wrong hands and be utilized against commercial aviation. That’s something that really worries me.

It has always worried me that Venezuela is a failed state. I used to call Maduro the mayor of Fort Tiuna, the military base he lives on, because he has no control over the rest of the country. They sent the military into Apure, near the border with Colombia, and they lost 19 soldiers in combat with the ELN. It was one of the largest losses of life in the military’s history. They can’t control their own territory. And we don’t have a good partner in President Petro. I envision a scenario in which we can’t convince Petro to take a more proactive role in stopping cross-border activity. In fact, I’ve heard that the leaderships of FARC-D, a dissident FARC, and ELN—two Marxist, foreign terrorist, drug-trafficking organizations—have left Venezuela and gone back into Colombia to avoid being directly targeted by the United States. So this is a problem.

Then there are all the unknown unknowns that happen as you move forward with something like this. I do think that the trend will be toward a stable democratic country, which is a net positive for the region. But it’s going to require financial investment and investment of our attention. This is not going to be “Maduro’s gone and everything is perfect.” It took three to six months to get Panama under control. It’s a tenth the size of Venezuela. But I do think the ultimate outcome is going to be a democratic, stable country.

RA: So much of this depends on longer-term commitment, as you’ve been pointing out. This is a good moment to come back to the Monroe Doctrine. What is your sense of how committed Trump is to the idea of U.S. supremacy in the Western Hemisphere? And within that, where does Venezuela fall? There are a lot of people who would point out that this project we’re seeing right now is mostly led by Marco Rubio, the secretary of state and the national security advisor, and that Trump may actually not be that willing to see this through. How do you see all of this?

JS: The president’s been willing to act before. He saw the attack on [Iranian Gen. Qassem] Suleimani, for instance, as an ultimately low-cost, high-yield action.

He could be willing to do something like that in Venezuela. What happens in the Western Hemisphere is the most important thing to the United States. I spent my career in the Western Hemisphere, and things that happen in Central America and South America have a direct impact on us. Having a focus on the Americas is important. How that focus is laid out in practice is equally important.

But your question really is about how far is President Trump willing to go. I don’t think he’s willing to invade Venezuela or any other country in the hemisphere. I think he views war generally as unprofitable. But I do believe he’s willing to do things to make the region more favorable to American interests. That’s perhaps a part of the rationale behind pardoning Juan Orlando Hernández, for the elections in Honduras. Perhaps that’s the reason behind a $20 billion bailout for the Argentine peso. Perhaps that’s the reason why he no longer talks about [former President Jair] Bolsonaro but instead is engaging President [Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva] in Brazil on critical minerals, which is extraordinarily important for us and the region. But all of the problems in the hemisphere are kind of exemplified by what’s happening, to some extent, in Venezuela. It’s the perfect example of how everything comes together in a very bad way.

RA: Are we locked into some form of military action, now that Trump has this big armada there? Because were nothing to take place, Maduro could say he withstood the might of the greatest military in the world and could double down and stay in power even longer.

JS: If we don’t act, there is a huge risk of undermining American credibility more broadly. That’s why I have the odds of military action at 80-20.

But I want to go back to this Trump corollary to the Monroe Doctrine. We can still make a deal. As a former diplomat and retired ambassador, I’m all about dealmaking. I believe in the power of negotiation. In fact, I would submit that the negotiations under the Biden administration led to the primary that María Corina Machado won. It led to mistakes made by the regime to allow an election, which they lost. Those are good outcomes. They came because negotiations created space for them.

But the floor of a negotiation has to be Maduro leaving. I’m happy to negotiate what airplane he gets on and how much baggage he can take with him. I’m happy to negotiate an interim government model that has the elected president, Edmundo González, but also has room and space for lots of different political thought. But there will be transitional justice as part of it, some program that allows for some amnesty of action, or it won’t get off the ground.

Don’t miss more hot News like this! Click here to discover the latest in Politics news!

2025-12-19 17:49:00