Solving sparse finite element problems on neuromorphic hardware

Finite element problem

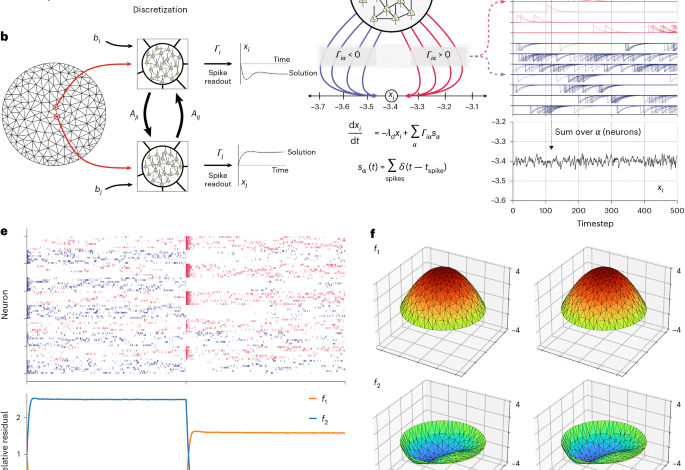

We evaluated our FEM network on a specific PDE problem, the steady-state Poisson equation on a disk, with Dirchlet boundary conditions:

$$^-\leftu=f\,\mathrm\,\varOmega;$$

$$u=0\,\mathrm\varGamma \right\,\partial \varOmega .$$

Unstructured finite element meshes were generated with the MeshPy library, which provides a Python interface to the Triangle package40. We generated meshes with different resolutions by setting the maximum triangle area parameter in the mesh generation process.

We assembled sparse linear systems (the stiffness matrix and mass matrix) using piecewise linear elements directly from their definitions using the NumPy and SciPy libraries.

For our accuracy and convergence evaluations (Figs. 2 and 3), we used a constant forcing function

$$f\left(x,y\right)=-20.$$

For this specific f, the problem has an analytic solution:

$$u\left(x,y\right)=5\left(1-\varGamma \right^\varGamma \right-^\left\right).$$

For Fig. 1e, we evaluated the solution with a different forcing function defined by

$$f\,(x,y)=12-60\varGamma \right^-60-\left^-\left.$$

Discretization of these problems on our meshes with piecewise linear elements yields a sparse linear system Ax = b, where A is an (nmesh, nmesh) sparse matrix.

SNN

Our SNN consists of neurons implementing generalized leaky integrate-and-fire dynamics. Readout neurons implement leaky integration of spikes \(\varGamma \right_\left\) into real-valued output variables xi through a readout kernel Γ through the differential equation

$$\frac\varGamma \right-\left=-\varGamma \right_\varGamma \right\varGamma \right_\varGamma \right+\mathop-\left\limits_\left_\varGamma \right\,{{\bf\varGamma \right}_\varGamma \right}\left(t\right).$$

Γ is our readout matrix that maps individual neurons to the variables of the linear system. For each mesh point, we associate a fixed quantity of neurons (npm; neurons per mesh point); thus, Γ has shape nmesh × (nmesh × npm). Non-zero elements in each row i of Γ correspond to neurons that project to the associated output variable xi. Thus, there are npm non-zero elements per row. Half of these non-zero elements have magnitude +|Γ|, corresponding to neurons projecting with positive weight (Fig. 1c) and half have magnitude –|Γ|. Thus, Γ has the form

$$\left[\begin{cccccc}+\left|\varGamma \right| & -\left|\varGamma \right| & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0\\ 0 & 0 & +\left|\varGamma \right| & -\left|\varGamma \right| & 0 & 0\\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & +\left|\varGamma \right| & -\left|\varGamma \right|\end{array}\right],$$

where each non-zero block is a (1 × npm/2) constant block with the indicated values.

There are two classes of synapses between neurons. ‘Slow’ synapses communicate information between mesh nodes and are termed slow because their signals undergo two integrations into the neuron’s membrane potential. The slow synaptic weights are defined by

$${\varOmega }_{\mathrm{slow}}={\varGamma }^{\mathrm{T}}A\varGamma ,$$

where Γ is the readout matrix, ΓT is the readout matrix and A is the system matrix. Ωslow is block structured and sparse. Each non-zero block of Ωslow corresponds to a non-zero element of A. Each non-zero block of Ωslow has the structure

$${A}_{{ij}}\left[\begin{array}{cc}{\left|\varGamma \right|}^{2} & {-\left|\varGamma \right|}^{2}\\ {-\left|\varGamma \right|}^{2} & {\left|\varGamma \right|}^{2}\end{array}\right].$$

The entries in the 2 × 2 matrix above represent constant submatrices with shape (npm/2) × (npm/2). Even though Ωslow is already sparse, there is still redundancy in its definition, and future implementations of the network may benefit from reducing this redundancy using shared synapses.

The second class of synapses are called ‘fast’ because they are singly integrated. They communicate entirely within mesh nodes and accomplish fast coordination between neurons within a node. The fast synaptic weight matrix is defined as

$${\varOmega }_{\mathrm{fast}}{=}{\varGamma }^{{T}}\varGamma .$$

Because of Γ’s structure, Ωfast is block diagonal and each block has the form

$$\left[\begin{array}{cc}{\left|\varGamma \right|}^{2} & {-\left|\varGamma \right|}^{2}\\ {-\left|\varGamma \right|}^{2} & {\left|\varGamma \right|}^{2}\end{array}\right].$$

Slow synaptic input is first integrated into a latent state variable within each neuron (u1) with time constant λd, according to the equation

$$\frac{{\rm{d}}{u}_{1,\alpha }}{{\rm{d}}t}=-{\lambda }_{d}{u}_{1,\alpha }+\mathop{{\sum }}\limits_{{\beta }}{\varOmega }_{\mathrm{slow}{,}{\alpha }{\beta }}\,{{\bf{s}}}_{\beta}\left(t\right).$$

Here, s(t) represents the vector of Dirac delta spike trains from other neurons in the network. Fast synapses are similarly singly integrated into a separate latent variable u2 with the equation

$$\frac{{\rm{d}}{u}_{2,\alpha }}{{\rm{d}}t}=-{\lambda }_{d}{u}_{2,\alpha }+{\lambda }_{d}\mathop{{\sum }}\limits_{{\beta }}{\varOmega }_{\mathrm{fast},\alpha \beta }\,{{\bf{s}}}_{\beta}\left(t\right),$$

where u1 represents the neuron’s local evaluation of the left-hand side of the linear system (Ax). A neuron’s component of the difference between the left-hand side and right-hand side of the linear system (the residual) is computed locally and carried by the latent variable uerr. Here, b is the right-hand side of the linear system and acts as a bias current for each neuron:

$${u}_{\mathrm{err},\alpha }={-u}_{1,\alpha }+{\varGamma }^{T}{\bf{b}}.$$

Each neuron acts as a proportional-integral (PI) controller (and integral dynamics are necessary for accurate spiking solutions), so each neuron has a state variable uint that tracks the integral of the error:

$$\frac{{\rm{d}}{u}_{\mathrm{int},\alpha }}{{\rm{d}}t}={u}_{\mathrm{err},\alpha }.$$

Finally, all these quantities are combined into a differential equation for the membrane potential v:

$$\frac{{\rm{d}}{v}_{\alpha }}{{\rm{d}}t}=-{\lambda }_{v}{v}_{\alpha }+{k}_{p}{u}_{\mathrm{err},\alpha }+{k}_{i}{u}_{\mathrm{int},\alpha }+{u}_{2,\alpha }-\mathop{\sum }\limits_{\beta }{\varOmega }_{\mathrm{fast},\alpha \beta }\,{{\bf{s}}}_{\beta}\left(t\right)+{\sigma }_{v}{\eta_{\alpha }}.$$

Here, η is a vector of independent samples from a Gaussian distribution. The parameter σv is the standard deviation of the noise, which we set to 0.00225 for all networks.

Neurons emit a spike when their membrane potential v reaches a threshold value θ. The threshold is defined by

$$\theta =\frac{1}{2}{\left|\varGamma \right|}^{2}.$$

Upon spiking, neuron membrane potentials are reset by subtracting the threshold value.

Because the spiking network implements the dynamical system

$$\frac{{\rm{d}}\bf{x}}{{\rm{d}}t}=\bf{b}-{A \bf{x}},$$

the convergence of the network depends on the spectral properties of the matrix \(A\). The eigenvalues of \(A\) determine the intrinsic timescales of the network. If all the eigenvalues are of the same sign (that is, the matrix A is definite), the dynamics will converge to a fixed point.

CPU simulations

We simulated the above equations using Python. The above differential equations were integrated using the forward Euler method with a timestep dt = 2−12.

Spiking network evaluation

We evaluated our spiking network by comparing spiking solutions both with the analytic solution for our test problem and with solutions produced by a conventional linear solver (SciPy spsolve function). We ran each network for 50,000 timesteps to ensure the network converged to steady state. We then extracted the spiking network’s estimate of the solution by averaging the readout variables over the last 10,000 timesteps.

For all error estimates, we use the L2 norm. We computed the relative error between the analytic solution on the mesh points and either the spiking or conventional solver using the equation

$$\mathrm{RelErr}=\frac{\Vert \hat{\bf{x}}-{\bf{x}}\Vert }{\Vert {\bf{x}}\Vert }.$$

Here, \(\hat{x}\) represents either the spiking or conventional solution and \(x\) represents the analytic solution.

We evaluated the relative residual of the linear system per mesh node (Fig. 2d) for the spiking network by computing the quantity

$$r=\frac{1}{{N}_{\mathrm{mesh}}}\frac{\Vert {\bf{b}}-A\hat{\bf{{x}}}\Vert }{\Vert {\bf{b}}\Vert }.$$

Loihi 2 implementation

We implemented the dynamical systems defining each neuron described by the equations above using custom microcode neurons on Loihi 2.

To map the parameters of our spiking network onto Loihi 2, we first converted the above equations from floating point to fixed point. To do this, we rescaled the above equations (as described in ref. 12) so that the numerical values of the fast and slow weight matrices were contained in intervals bounded by a power of two (arbitrarily chosen).

Next, we introduced power-of-two scale factors for each parameter and state variable. Generically, if x refers to a parameter or state variable in the floating-point model, we relate x to its fixed-point counterpart (denoted \(\bar{x}\)) using the relation

$$\bar{x}=x\times {2}^{{s}_{x}}.$$

Fixed-point quantities denoted with overbars are rounded to the nearest integer. After defining the associated fixed-point variables for each floating-point variable, we substituted the corresponding fixed-point quantity into the above equations. This substitution brought the associated scale factors into the above differential equations. We algebraically rearranged these scale factors so that the left-hand sides of each equation were written entirely in terms of fixed-point quantities.

This algebraic rearrangement leads to power-of-two scale factors multiplying each quantity on the right-hand sides of the equations. These factors are the conversion factors between the scales of the different fixed-point quantities in the equations. Because these conversion factors are, by definition, powers of two, we implemented them on Loihi 2 by incorporating specific bit-shift instructions into our microcode neurons.

We chose the exponents in the scale factors by considering the allowed precision of different variables on Loihi 2. For example, synaptic weights on Loihi 2 have 8-bit precision. Thus, we chose the scale factor so that our final weight matrix would take the values in the range [–128, 127]. Similarly, state variables on Loihi 2 have 24 bits of precision, so we selected scale factors for each dynamical variable to ensure that its dynamic range utilized as much of the available range of the corresponding fixed-point representation as possible. Once scale factors were chosen, the fixed-point equations determined the precise form of the microcode with all the required bit shifts to rescale variables to compatible fixed-point representations.

Loihi 2’s pseudorandom number generators produce uniformly distributed 24-bit integers. Because the floating-point model assumed a Gaussian noise source with a specified standard deviation, we scaled the Loihi 2-generated random number so that the standard deviation of the uniform random numbers approximated that of the Gaussian noise source in the floating-point model, written in the scale of the neuron membrane potential.

|

Parameter |

Scale factor |

|---|---|

|

Ωs |

26 |

|

Ωf |

219 |

|

Γ |

213 |

|

v |

228 |

|

bias (ΓTb) |

217 |

|

u1 |

216 |

|

u2 |

220 |

|

uerr |

216 |

|

uint |

220 |

|

x (readout) |

216 |

We chose the parameters Kp, Ki, λd, λv and dt to be powers of two, allowing their multiplication to be implemented as simple bit shifts in the fixed-point representation. These bit shifts were folded into the shifts resulting from differences in fixed-point scale factors.

|

Parameter |

Value |

|---|---|

|

Kp |

22 |

|

Ki |

24 |

|

λd |

23 |

|

λv |

24 |

|

dt |

2−12 |

In Loihi 2, spikes from adjacent neurons are accumulated after weight multiplication into registers called dendritic accumulators. In our network, each neuron uses two dendritic accumulators to accumulate the slow and fast synaptic inputs separately. We refer to these accumulators as DAslow and DAfast. The final fixed-point equations defining Loihi 2 neuron updates on each timestep (n) are as follows (here, » indicates arithmetic right shift and « indicates arithmetic left shift):

$$\overline{{u}_{1}}[n+1]=(511\times \overline{{u}_{1}}[n])\gg 9+{\mathrm{DA}}_{\mathrm{slow}}\ll 10;$$

$$\overline{{u}_{2}}[n+1]=(511\times \overline{{u}_{2}}[n])\gg 9+{\mathrm{DA}}_{\mathrm{fast}}\gg 5;$$

$$\overline{{u}_{\mathrm{err}}}[n+1]=\overline{{u}_{1}}[n]+(\overline{{\varGamma }^{T}b})\ll 7;$$

$$\begin{array}{l}\overline{v}[n+1]=(255\times \overline{v}[n])\gg 8+(\overline{{u}_{\mathrm{err}}}\ll 2)+\overline{{u}_{\mathrm{int}}}\\ +(\overline{{u}_{2}}\gg 4)-({\mathrm{DA}}_{\mathrm{fast}}\ll 9)+(\overline{n}\gg 3).\end{array}\,\,$$

Loihi 2 chips contain 128 neural cores. We mapped our network onto these cores by placing the neurons belonging to a single mesh node onto the same core, proceeding core by core and node by node (round robin). We wrapped the node-to-core mapping upon reaching the maximum number of cores per chip, such that the core index c containing neurons for mesh node index m is given by m = c mod 128. This is a naive layout of the network on the chip, and the network could benefit from a layout that respected the geometric adjacency relations between mesh nodes.

Loihi 2 evaluation

We ran NeuroFEM circuits for mesh sizes in the range of 100–1,000 to ensure the circuits fit onto a single Loihi 2 chip. For each mesh resolution, we ran the circuits for 10,000 timesteps and computed the average value of the readout over the last 1,000 timesteps. To quantify the accuracy of the Loihi 2 generated solutions, we computed the relative errors and residuals using the same formulae described above for the floating-point CPU simulations.

Loihi 2 profiling

To profile the networks on Loihi 2, we used the same meshes as in our evaluations, but we turned off all hardware input and output (I/O) so that I/O was excluded from power and time measurements. Because the dynamics of the circuit relax to a steady-state solution, the real ‘work’ in solving the linear system happens during transients in the execution upon a change in the bias (right-hand side). To profile these transients, we set up our profiling runs to alternate between two different right-hand sides by flipping the sign of the bias every 4,096 timesteps. Because the system is linear, the resulting solutions are sign-inverted mirror images of each other. This means that, during the solution transient, the activity in the network shifts from one set of neurons to the complementary set of neurons.

We performed two sets of profiling runs, which we term “steady state” and “transient.” During steady-state runs, the biases were multiplied by +1 every 4096 timesteps, so the biases did not change, and the network remained in its steady-state firing regime. During transient runs, we multiplied the bias by –1 every 4096 timesteps. Thus, the network was forced to flow to a new steady state. We implemented these multiplications directly in the microcode, allowing the network to update its own bias without any I/O requirements, and ensuring that both steady-state and transient runs executed the same instructions. We call the 4,096-timestep windows around each sign inversion a solution epoch.

Each run, either transient or steady state, lasted for 32 solution epochs or 131,072 timesteps. We used Loihi 2’s built-in power measurement interface to record the power/energy used by the entire run. We then divided the total energy and wall time consumed by the number of solution epochs to estimate the average energy and wall time required per solution epoch.

By comparing the energy per epoch from both transient and steady-state runs, we were able to estimate the average excess energy and time required by the solution transients as the network computed a new solution (Fig. 3). Comparing against networks that remained in steady state allowed us to subtract the steady-state power.

Multi-chip scaling on Loihi 2

For multi-chip studies, we used all 32 chips on the Intel Loihi 2 platform while varying the number of cores used per chip and the number of meshpoints nmesh. To partition our mesh across chips, we used a greedy heuristic scheme that, while not guaranteed to provide an optimal partitioning, was effective at reducing interchip communication. Using our 2D mesh as an example, this approach worked as follows:

This partitioning is run for 16 iterations. While there is no guarantee of stability or speed of convergence, we observed that for 32 chips the partitioning was stable for our purposes (Fig. 4a). Within each chip, mesh points were assigned to available cores in a round robin fashion.

For strong-scaling experiments, we examined the impact of using more cores per chip for several fixed model sizes. Strong-scaling studies typically seek to identify a measure of speedup,

$$\mathrm{speedup}=\frac{T\left(1\right)}{T\left(N\right)}=\frac{1}{s+p/N},$$

where N is the number of processors, T(1) is the time for running on a single processor, T(N) is the time for running on N processors, and s and p are the serial and parallel proportions of the algorithm, respectively. In ideal strong scaling, p»s, and there is a near-linear speedup for increasing N up to the point that serial computation dominates.

In our experiments, because a single Loihi 2 core is limited to ~512 neurons, there was a minimum number of cores required for every experiment. This makes T(1) impossible to measure empirically; therefore, in our experiments, we assumed ideal scaling down to the serial level in the absence of core memory limitations. This linear assumption is justified by the linearity of the first few points in our results and the agreement between scaling curves for meshes of different sizes.

For weak-scaling experiments, we examined the impact of increasing the model size with an increased number of model cores. As with the strong-scaling studies, we measured efficiency by the ratio of a single-core sized model against increasing sized models.

$$\mathrm{efficiency}=\frac{T\left(1\right)}{T\left(N\,\right)}.$$

In weak-scaling experiments, the ideal behaviour is for time to be constant with increased model size because both size and resources are scaling together.

CPU profiling

CPU profiling of GMRES41 and CG42 conventional linear solvers was performed using standard SciPy implementations on Python. These analyses were performed on an Intel Xeon E5-2665 server class processor. Full details on this processor are available at ref. 43.

Linear elasticity example

In Fig. 5d–f, we evaluated a linear elasticity problem on a 3D tetrahedral mesh. The mesh was generated using the Gmsh package12 and consisted of 583 tetrahedra. The sparse linear system was assembled using SfePy16,17 and yielded a (3,627, 3,627) sparse matrix with 222,003 non-zero entries. We solved the resulting linear system using both SciPy spsolve and NeuroFEM using eight neurons per mesh node (network size: 29,016 neurons) and |Γ| = 2−6.

Specifically, we solved the following PDE system (in Cartesian coordinates):

Cauchy momentum equation

$$\nabla \bullet {\boldsymbol{\sigma }}+{\bf{F}}=0;$$

Tensorial Hooke’s law

$${{\mathbf{\sigma}}_{ij}}={\sum\limits_{kl}}{{C}_{ijkl}}{{\mathbf{\varepsilon}}_{kl}};$$

Definition of infinitesimal strain

$${{\mathbf{\varepsilon}}}={\frac{1}{2}}{\left[\nabla {\bf{u}}+{\left(\nabla {\bf{u}}\right)}^{T}\right]};$$

Definition of the stiffness tensor for a homogeneous, isotropic material

$${C}_{{i}{j}{k}{l}}=\lambda {\delta }_{{i}{j}}{\delta }_{{k}{l}}+\mu \left({\delta }_{{i}{k}}{\delta }_{{j}{l}}+{\delta }_{{i}{l}}{\delta }_{{k}{j}}\right);$$

where \({\boldsymbol{\sigma }}\) is the Cauchy stress tensor, \({\boldsymbol{\varepsilon }}\) is the strain tensor, \({\bf{u}}\) is the displacement vector and \(C\) is the fourth-order stiffness tensor. \({\bf{F}}\) is the force density (force per unit volume), which was constant in the –Z direction representing the force of gravity. The parameters \(\lambda\) and \(\mu\) are the Lamé parameters defining the material mechanical properties (both set to 1), and \(\delta\) is the Kronecker tensor.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Don’t miss more hot News like this! Click here to discover the latest in AI news!

2025-11-13 00:00:00